The Forgotten Faces of Hammer: Cybill Shepherd – Part Two

Part One was a tale of triumph and tragedy; star-crossed lovers and the end of an era. We traced Cybill Shepherd’s career throughout the 1970s, taking in The Last Picture Show, Taxi Driver, and her early forays into music before she climbed aboard Hammer’s final feature film of the twentieth century. Now we delve into the making of The Lady Vanishes, its unforeseen, major repercussions throughout cinema, and the continuation of Shepherd’s own astonishing journey. We also examine a novel beginning and see why Hammer director Anthony Page really was the best man…

The critical reaction to The Lady Vanishes is often misremembered with more than one retrospective terming the work ‘much maligned’. Filmink’s assertion that the movie ‘received horrendous reviews’ is not an atypical observation, but it’s a potentially misleading one. In actuality, Hammer’s final feature of the 70s won a huge amount of praise from reviewers. On Film declared, ‘This film comes off beautifully’, the Daily Mirror called it, ‘suspenseful and thrilling’ and The New Statesman enthused it was, ‘A pretty skilful, appealing and courageous job.’ The News of the World agreed it came across as, ‘a delightful film’ and The Sun shone on the picture, pronouncing it, ‘good rollicking stuff’.

Despite these accolades it performed poorly at the box office and the general feeling was that it had suffered the fate of many Hitchcock remakes, with audiences suspecting the original could never be topped, and therefore avoiding any film that had the nerve to try. (See also 1996’s Psycho, 1993’s Life Pod, and many more.) The previous year had seen The 39 Steps (1978) drum up good business, but that production was marketed as less of a remake, and more a faithful adaptation of the original novel.

Angela Lansbury played Miss Froy, a role previously portrayed by Dame May Whitty. Aged 88, Lansbury herself was made a Dame in 2014 at an investiture ceremony at Windsor Castle.

But for this The Lady Vanishes, the Hitch hitch was undoubtedly a problem, albeit one which Michael Carreras had anticipated in advance, insisting his effort was ‘not a remake, but a remould’. Got that? A remould. Not a remake. Okay…

Screenplay writer George Axelrod also recognised the issue, shrewdly pointing out that, ‘We’re not competing with Hitchcock, but with people’s memories of the film.’ He was right. The Lady Vanishes (1938) is a marvellous, enduring piece of entertainment, but it has its faults. Unusually for one of Hitchcock’s 30s thrillers it takes an age to get going and its leading man, Michael Redgrave, plays a love interest who’s initially so selfish, arrogant and aggressive towards the central female character, that modern audiences are left wishing he’d vanished instead of the lady.

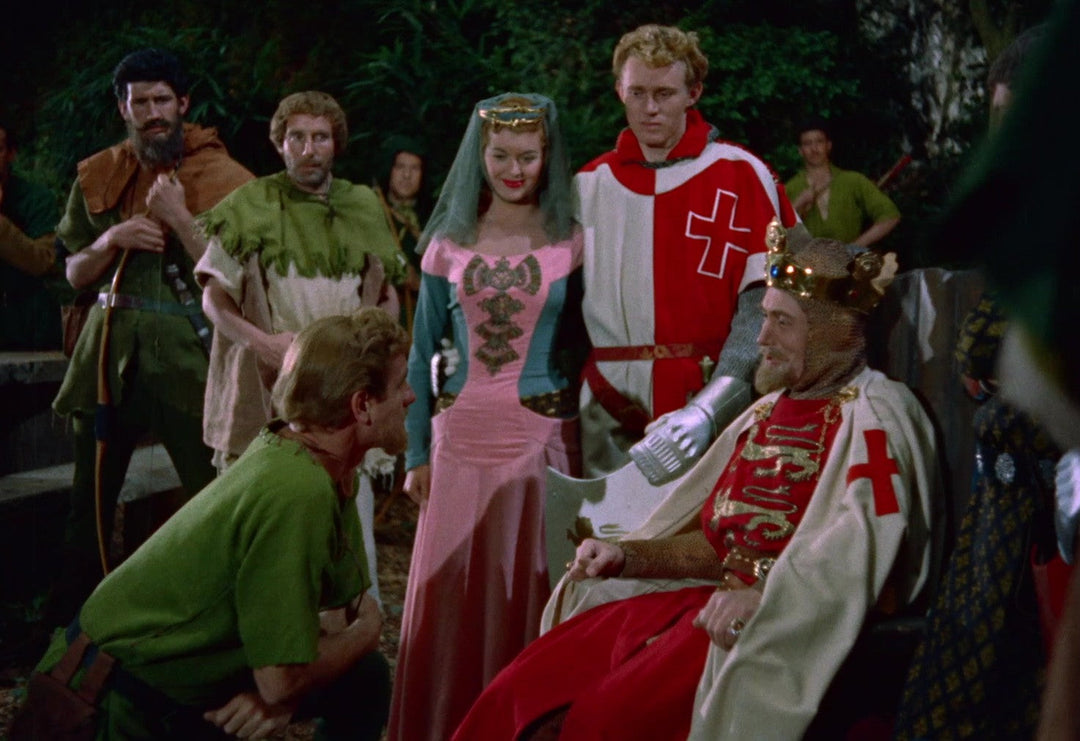

Shepherd with Arthur Lowe in a moment from The Lady Vanishes, which was not a remake. Repeat: not a remake…

Hammer’s version plunders what was so good about the original, including the magnificent double act of the cricket obsessed Charters and Caldicot (here played by Arthur Lowe and Ian Carmichael), the rather tragic couple of Mr Todhunter and his companion, and of course, the overall story which remains largely intact. Most of the narrative changes are sage. It’s set in August, 1939 as opposed to the previous year, making the NAZI threat much more immediate. The shadow of conflict that features in Hitchcock’s original is now the harsh glare of imminent war. When Shepherd’s character, Amanda, spoofs Hitler, his thugs in uniform unhesitatingly respond by physically attacking her with precious few repercussions. This is very nearly their world, with all the violence and injustice such a nightmare entails, making the setting in this version infinitely more troubling and dangerous.

Redgrave’s Gilbert becomes Gould’s Robert, a mercifully toned-down character who’s a photojournalist, as opposed to a semi-drifter that feels inexplicably compelled to bother people with loud, local folk music. The plot speeds along at a greater pace and the visuals are in many ways superior, with the extensive shoot in Austria paying dividends and expertly captured by cinematographer Douglas Slocombe whose previous work included The Lavender Hill Mob (1951), The Servant (1963), The Italian Job (1969) and The Great Gatsby, which Shepherd had so nearly been a part of. (Following this production he’d lend his talents to the first three Indiana Jones flicks, winning an Academy Award nomination for 1981’s Raiders of the Lost Ark). Obviously, the Hammer film is in colour and the model work that looked charming, but almost brazenly artificial in the 1938 version, is nowhere to be seen.

All this resulted in Cosmopolitan stating Hammer’s Lady was a ‘sparkling thriller… better than the original’ and The Guardian noting it moved at ‘A faster pace than Hitchcock.’

Some film historians have suggested the two lead roles were originally intended for George Segal and Ali MacGraw. Ultimately, of course, the parts were played by Elliott Gould and Cybill Shepherd.

The chief narrative difference, in terms of the earlier picture, is the main character, as played by Shepherd. An Englishwomen named Iris in both the original film and the novel by Ethel Lina White, here she’s an American called Amanda Kelly. But despite the change of nationality, Shepherd captures more of the book’s protagonist, whom White evocatively described in the opening chapter of her most famous novel:

‘She was used to the protection of a crowd, whom—with unconscious flattery—she called ‘her friends.’ An attractive orphan of independent means, she had been surrounded always with clumps of people… Their constant presence tended to create the illusion that she moved in a large circle, in spite of the fact that the same faces recurred with seasonal regularity. They also made her pleasantly aware of popularity. Her photograph appeared in the pictorial papers through the medium of a photographer’s offer of publicity, after the Press announcement of her engagement to one of the crowd… This was Fame.’

And shortly after that passage: ‘To these six persons [her companions], Iris appeared just one of her crowd, and a typical semi-Society girl—vain, selfish, and useless. Naturally, they had no knowledge of redeeming points—a generosity which made her accept the bill, as a matter of course, when she lunched with her ‘friends’, and a real compassion for such cases of hardship which were clamped down under her eyes.’

In the novel, one passenger says of Shepherd’s character, ‘That sort of girl is utterly selfish. She wouldn’t raise a finger, or go an inch out of her way, to help any one.’ The line emphasises how looks can be highly misleading.

Shepherd sensitively captures all this, plus Amanda’s privilege and the confidence it’s given her. When we meet her, she believes she’ll be fine simply because she’s always been fine. The war will, she expects, be nothing but a minor inconvenience to her personally, and she seems curiously unaware of the danger she puts herself in by parodying Hitler in front of brown-shirted soldiers. Shepherd turns Amanda’s entitlement into a kind of shell that surrounds her. Insulates her. She’s tougher than the Iris in Hitchcock’s film, so when we see her warmth towards Miss Froy it’s a heartwarming moment as we begin to appreciate that she isn’t simply the ‘vain, selfish, and useless’ semi-Society girl she masquerades as.

Shepherd never reaches for our affection. During the opening scenes of the film especially, prior to her departure from the village, she ensures Amanda is cold and unfeeling at times, never warming her with a winning smile or a glimpse of hidden vulnerability. Those qualities emerge as the train, and the movie, continues on its journey, but it’s a natural evolution and never a sympathy play. It means Hammer’s final filmic heroine of the twentieth century emerges as a flawed but independent woman who’s kind and considerate, and undeniably brave when searching for her lost friend. She’s a million miles from the ‘little lady’ stereotypes who feel the need to be constantly what other people want her to be, and Amanda reckons she doesn’t need help from other passengers to complete her quest. When she lets Robert assist her, she’s doing him a favour, not the other way around.

Some of this is in the script, of course, but Shepherd conveys and amplifies it beautifully and truthfully. When Amanda finally talks about a man she might have loved, for example, she manages to make the implicit fragility not of herself, but belonging solely to the fractured relationship. It’s one of many scenes she plays with an adroit authenticity that adds enormously to the film’s appeal.

The presence of Herbert Lom brings to mind Hammer movies of previous decades, and he’s a welcome addition to the cast of The Lady Vanishes.

Herbert Lom portrays Dr Hartz with old school menace, and the sparkling Angela Lansbury is fabulous as Miss Froy. It’s been said that Elliott Gould was miscast and had no chemistry with Shepherd, but the real shame is that the script didn’t have the courage to make their characters platonic pals. They work just fine as friends – credibility is only stretched when we’re asked to believe they have romantic inclinations towards each other.

Gould was to prove problematic for Shepherd, as well. In her autobiography she remains respectful of him but recalled he was ‘…mercurial, seemingly detached from the process and easily miffed.’ Clearly she got along much better with her other colleagues. She spoke fondly of Lansbury and revealed they sang Gershwin songs together between shots. (They remained friends and the veteran offered her useful advice when her career took her into television.) And when Shepherd married David Ford before returning to the States, Michael Carreras walked her down the aisle and director Anthony Page was the best man.

There’s something affirming and almost magically apt about that in itself. It means the closure of Hammer didn’t end with a wake, but with wedding celebrations, completely in keeping for an organisation that had, in one way and another, brought so many people together over the decades and was often described as a family.

As for The Lady Vanishes… It vanished. At least for a while. It seemed to endure a spell of critics comparing it unfavourably to the original, but in recent years it’s become a favourite of many. It feels odd to acknowledge that in 2025, the film was made 46 years ago, meaning its production was closer to the war it uses as a backdrop than it is to contemporary audiences. In other words, the film is now nearer to its setting (and Hitchcock’s version) than it is to us. Perhaps that’s what allows us to see the pictures in an historical context. To love this Hammer production whilst still adoring the original. And if such duality of thought seems unfitting, the words of one critic talking about The Last Picture Show become a useful reminder: ‘The only hope is in transgression.’

On location - Cybill Shepherd in ‘that dress’.

Cybill Shepherd is such a talented performer she probably didn’t need Hammer’s help to further her career, but her work on The Lady Vanishes resulted in the role that she’s most remembered for. Because in the early 80s, as Glenn Gordon Caron wrote the pilot of Moonlighting, halfway through the script he recalled Shepherd in what he reportedly referred to as ‘that dress’. He was referring to the iconic, white satin bias cut frock she wore in The Lady Vanishes that Shepherd had also loved, believing it captured the Carole Lombard look to a tee. (There were nine identical copies of this item of clothing as it was virtually the only thing Amanda wears in the course of the story!) And with Caron’s recollection of that resourceful, gritty but glamourous woman, he realised that was Maddie Hayes. The female lead character for his new series. Yes, that was Maddie. And that was Cybill Shepherd.

Even before finishing the screenplay he met up with her and pitched the show. She recognised the premise immediately and told him, ‘I know what this is… it’s a Hawksian comedy,’ and at her suggestion, along with Caron and co-star Bruce Willis, they watched a number of screwball classics like Bringing Up Baby (1942) to ensure the tone of their show was a throwback to those great movies of Carole Lombard, Katharine Hepburn, and Rosalind Russell.

Marketing material for Bringing Up Baby, an inspiration for how Shepherd’s detective show, Moonlighting, should hit.

Thanks in large part to Cybill Shepherd, Moonlighting became one of the most successful programmes of the 1980s. Willis may have scooped more awards for his role of David than Shepherd won for playing Maddie, but without her, the show didn’t work. When she was forced to be absent from later episodes, for example, ratings slumped. She threw herself into the programme’s slapstick comedy but also delivered big on the dramatic moments. To watch her performance in episodes such as In God We Strongly Suspect (which deals with Maddie’s perception of her own aging and place in the world) is to find a thoughtful actor who’s unafraid to show cracks of authentic fear. Such performers only come along once in a Blue Moon.

The show which Shepherd helped to make, certainly made Bruce Willis. In a reunion special he reflected that if she’d not needed time off owing to a pregnancy, he wouldn’t have got to make Die Hard (1988). And this revelation illuminates a strange quirk of cinema. If it hadn’t been for The Lady Vanishes (which led to Shepherd’s casting in Moonlighting) there would have been no Bruce Willis in Die Hard. Who knows if the franchise would have succeeded without its eventual lead, but it seems unlikely his best-known movie would have landed so completely. And so Hammer’s 1979 comedy-thriller is responsible for the film that shaped the core identity of action movies throughout the close of the twentieth century and beyond.

So without this, Nakatomi Tower would have been safe, right?

Hammer heavyweights James Carreras, Anthony Hinds, Jimmy Sangster, and Michael Carreras might have appreciated that. Hell, they’d probably have wanted a piece of the action if they’d all been making movies together during that period. Hammer does ‘Die-Hard-in-a-haunted-house’. Who knows, maybe they could have persuaded Shepherd to play the lead, opening the door for a US financing deal…

Shepherd won two Golden Globes for her work on Moonlighting. The show ended in 1989 and she returned to feature films, including the sequel to The Last Picture Show, the 1990 follow-up, Texasville. It tanked at the box office and Filmink deemed it a ‘bad film’, although they praised the ‘Excellent acting from Cybill Shepherd (whose part should have been bigger)…’ Bogdanovich’s extended version - two-and-a-half hours and presented in black-and-white – fared much better. Writing for The Reveal, Scott Tobias commented, ‘While I would not say the director’s cut is a revelation—the word “rudderless” still applies to much of it—it’s a significant improvement, a big-hearted and philosophical slice-of-life that at least justifies its existence.’

In 1995 Shepherd played a version of herself, Cybill Sheridan, in the TV hit, Cybill, which ran until 1998 and earned her an impressive third Golden Globe Award as Best Actress in a Television Series - Musical or Comedy.

‘I never wanted to be Jane. I always wanted to be Tarzan. I didn't want to vacuum the tree house. I wanted to swing from the vines.’ – Cybill Shepherd.

Since that sitcom she’s appeared in numerous films and TV shows, released more albums and in 2012, she made her Broadway debut in Gore Vidal’s The Best Man, starring opposite James Earl Jones and Kristin Davis. She continues to thrive on the stage and has appeared in several critically acclaimed one-woman shows. Her latest, a cabaret-style production in which she ‘shares the soundtrack of her life’ is named after a title Joan Rivers gave her and which, with typical good humour, she immediately embraced: Queen of the Lucky Club.

Detractors may mock the moniker but they ignore the fact that it takes more than luck to enjoy success, relevance and respect in show business for more than fifty years. Over five decades after she dazzled audiences in The Last Picture Show, and over four decades since she took a train trip in The Lady Vanishes, Cybill Shepherd continues to draw audiences to her shows and to herself as an individual. In that 1975 interview she dealt with a question regarding bad reviews by telling the world, ‘I’d love to be loved by everyone. I mean, who wouldn’t?’ It’s half a century later and maybe, just maybe, somewhere on the way, she got her wish.