Coming Soon from Hammer Films: The Men of Sherwood Forest

As the old ditty goes, ‘Robin Hood, Robin Hood, coming to Blu-Ray / Robin Hood, Robin Hood – restored and in 4K…’ Yes! It’s been confirmed that the colourful, feel-good historical romp, The Men of Sherwood Forest (1954), will soon be released as part of Hammer’s Limited Collector’s Edition range.

We saddled up and galloped over to Hammer Towers to get the inside story from Steve Rogers…

Hammer News: I suspect this is the film that will surprise people the most out of any in the range so far. It’s such a well-made, fun and spirited movie. But it’s a complete departure from the kind of titles Hammer have restored and released so far. What was the thinking behind this one?

Steve Rogers: Historically it’s a milestone as it’s Hammer’s first colour feature film and, to echo myself from previous Q&As, it shows another facet of Hammer’s output – this time being the swashbuckling adventure story, a genre they returned to time-and-again over the next two decades.

Don Taylor as a Robin Hood more interested in his lute than his loot.

HN: Cool. I’ll come back to those points in a second, but let’s deal with the basics, first. Can you reveal a little about the plot of The Men of Sherwood Forest?

SR: Richard the Lionheart is imprisoned in Germany. A message that’s vitally important to the King’s safety is being couriered through Sherwood when the messenger is killed and the message stolen, Robin gets the blame, and he’s not best pleased about it.

HN: I can imagine. And more importantly, can you expand on the feel and tone of the film? There have been dozens of Robin Hood pictures over the years, from the grim but engrossing Robin and Marion (1976) to the light-hearted shenanigans of The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). Tonally speaking, where does The Men of Sherwood Forest lie?

SR: It’s very much deep in the tights-wearing, thigh-slapping era of Robin Hood – but with a rollicking soundtrack by Doreen Carwithen, energetic direction from Val Guest and larger-than-life performances from just about everyone, it’s a fun and memorable romp.

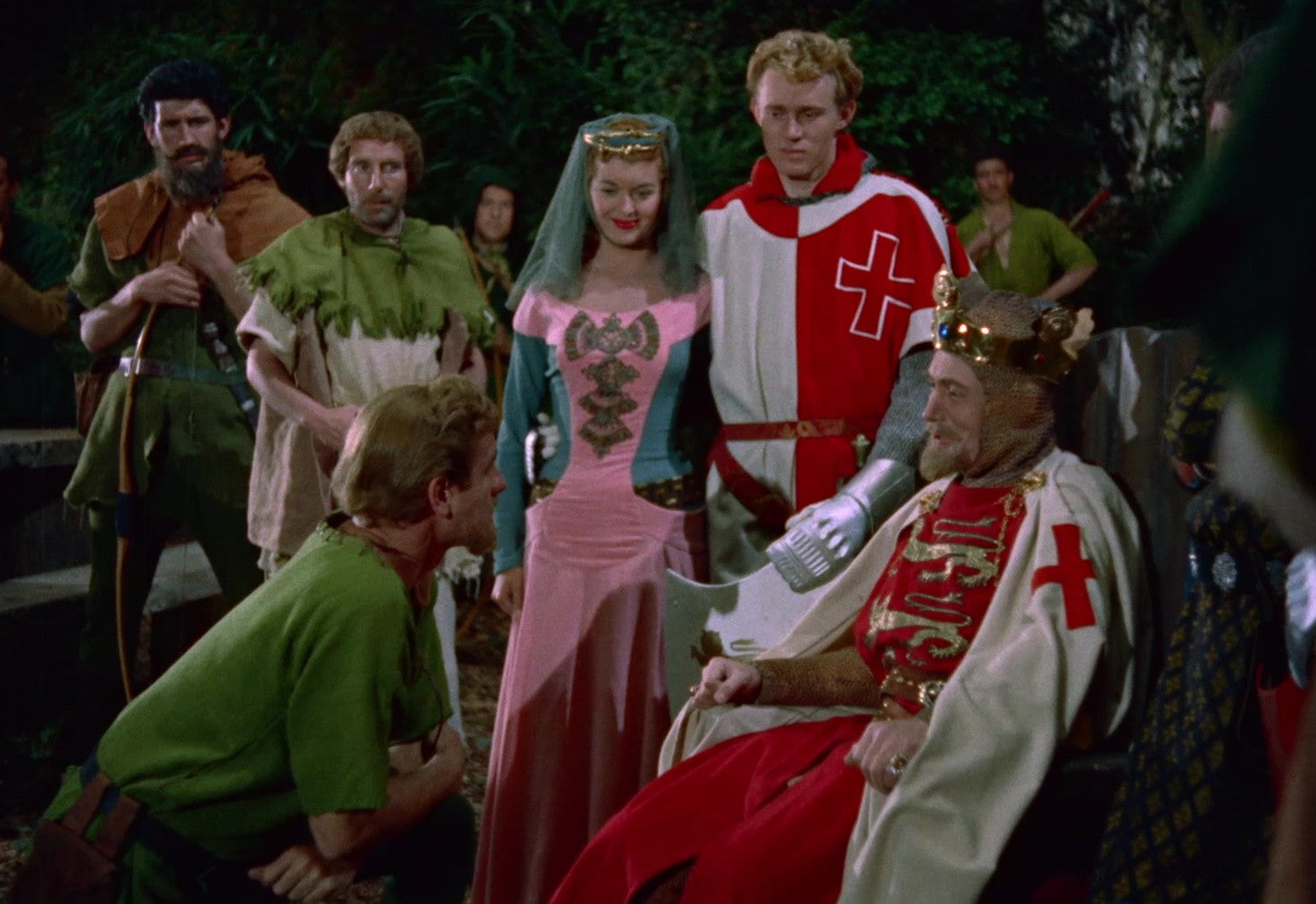

This (slightly blurry!) moment, showing Don Taylor and Eileen Moore, captures the sheer joy of The Men of Sherwood.

HN: The movie achieved a couple of firsts for Hammer. As you said, it was the first film of its genre to be released by the studio. Could you tell us why they plunged into this area when crime had served them so well since their post-war revival?

SR: One of the articles in the booklet attributes Hammer’s tacking away from crimers this once to the success of Walt Disney’s 1952 Robin Hood production with Richard Todd. I can’t argue with that assumption – Hammer at that time were great bandwagon-followers if there was obvious money to be made, and the swashbuckling genre served them well for another twenty years – from ’50s shorts like Dick Turpin and John Gilling’s “blood and thunder for rowdy schoolboys” (or whatever the actual quote was) feature films of the early ’60s through to the latter-day, genre-twisting TV pilot-turned-support feature, Wolfshead. Even though Wolfshead was an existing production they bought up, the fact that Hammer thought it would fit well into their schedule at a time when funds were scarce shows how highly they thought of the genre and its money-making potential.

HN: I’m curious. As you say, The Men of Sherwood Forest was successful enough to spawn, shall we call them ‘semi-sequels’? Critics were full of praise for the film, and it performed well at the box office. Why do you think it isn’t more widely known?

Marketing material for The Men of Sherwood. Douglas Wilmer (right) later shot to prominence playing Sherlock Holmes on television and in The Adventure of Sherlock Holmes' Smarter Brother (1975).

SR: I imagine because of its unavailability. Though Hammer revisited the swashbuckling genre regularly, I think I’m right in saying that it’s the last of those films to make it to home video – even though it was the first to be made. There’s no escaping the fact that, thanks to the sterling work of the William Alwyn Foundation, more people are now aware of Doreen Carwithen’s score from the film than the film itself. The opening theme even featured in last year’s Proms.

HN: Its other ‘first’ that you mentioned was arguably more significant than its genre. It was the very first Hammer feature film to be shot in colour. For context, plenty of black and white movies were still being made in the mid-50s, and hugely successful pictures like On the Waterfront (1954) and Marty (1955), were critically lauded and did good business. What I’m trying to say is that at the time, people were just fine with black and white movies, but Hammer decided to go down the route of colour, with all its added production complexity and, of course, expense. Why was that?

SR: It would have been, as with all Hammer production-centric decisions, purely commercial. With Disney’s full colour Sherwood romp fresh in people’s memories, Hammer would have calculated that doing this in black and white would be cheaper to make but would earn them less money. Plus, they would have had to try to make a colour feature at some point and this one had more financial potential than most. The fact that its use of colour is stunning and it informed what they would do only a few years later on The Curse of Frankenstein would have been incidental to the main profit motive.

Shooting began in May, 1954 and the film opened later that year, on 6th December.

HN: Funnily enough, I’d rewatched this film a few weeks before learning it was being restored, and it struck me that it simply wouldn’t work in black and white. Is that fair to say?

SR: That’s a fair comment. There are lots of black and white films that would lose something in colour – you couldn’t imagine The Man in Black or The Quatermass Xperiment in colour, for example, and it would be the same in reverse here. Everything from the lush colour palette used on clothing and furnishings to Lady Alys’s vermillion lipstick would be lost in monochrome – the colour is pretty much an additional member of the cast in this film.

HN: Don Taylor throws himself into the role of Robin with a gleeful gusto. How would you describe his performance in The Men of Sherwood Forest, and could you maybe tell us a little about his acting career outside this movie?

SR: Don Taylor – looking very Errol Flynn-adjacent here – is a charming and personable lead actor, having worked his way up through supporting character parts in films like Stalag 17 and Flying Leathernecks. He’s actually a very watchable actor but became disenchanted with acting soon after this and reinvented himself as a director on features and many, many episodes of television. It was while directing an episode of Alfred Hitchcock’s TV series that he met The Curse of Frankenstein’s Hazel Court, whom he would later marry.

Playing Robin Hood to a tee… Don Taylor has a quick cuppa between takes.

HN: These days Taylor is possibly better remembered for his directorial credits. Which of his films do you think people will know? And was he any good on the other side of the camera?

SR: People mainly remember him for his genre outings – Escape from the Planet of the Apes, the third in the original Planet of the Apes films, and the Omen sequel Damien – Omen II, which he took over from Mike Hodges. It would be hard to argue that any of his films were drop-dead classics but, like Terence Fisher, he had a non-stylish style that impressed through its professionalism and un-showiness.

HN: Getting back to The Men of Sherwood Forest, it boasts a terrific cast. We’ve got to start with Reginald Beckwith as Tuck, surely? What have audiences got to look forward to with his turn as the famous friar?

SR: In this particular adventure, for reasons which are not quite clear but reap huge rewards, Tuck is Robin’s main companion and there’s a very amusing undercurrent of whimsy that runs throughout the film – and Beckwith’s Tuck is the main beneficiary of that. If you’ve ever wondered how a monk with a gambling habit manages to convince a guardroom full of soldiers to disrobe then wonder no further!

Eileen Moore as Alys and Reginald Beckwith as Tuck. The latter made such an impact that there was talk of a follow-up, Friar Tuck, which sadly never materialised.

HN: Who else in the cast stands out for you – and why?

SR: There’s so much to choose from. Eileen Moore as the feisty Lady Alys, David King-Wood and the always-watchable Harold Lang as regicidal plotters, Patrick Holt as the Lionheart himself – as well as John Stuart, Bernard Bresslaw, Ballard Berkeley, Vera Pearce and others. Like most Hammers of this period it’s truly a roll-call of the best of the British character actors of the age.

HN: The past few years have seen a long overdue recognition and reappraisal of female composers. Fanny Mendelssohn is the obvious example, I guess. She seems to be much more discussed and played than ever before – even eclipsing her brother, Felix. Obviously, we’re talking about a completely different era, but the score for The Men of Sherwood Forest was composed by Doreen Carwithen, whom you referenced earlier. I have to confess, I wasn’t aware of her until recently. Could you tell us a little about her, and her style? And did she work for Hammer again?

SR: Doreen Carwithen is a world class composer who created such a memorable and rousing score for this film – a galloping, propulsive soundtrack that the film would be much diminished without. She made a name for herself as both a classical and film score composer, working on a couple more films for Hammer and over thirty films overall. I’m very pleased to say that we have a wonderful new programme on this release with Neil Brand, who visits Doreen’s archive at Cambridge University Library to learn more about this great composer and her score.

This was Eileen Moore’s only picture with Hammer. She also appeared in movies including The Green Man (1956) and the classic, An Inspector Calls (1954).

HN: Hammer’s Limited Collector’s Edition range has developed a reputation of having consistently outstanding additional material to contextualise, support and celebrate what I suppose could be termed the main feature. What have we got to look forward to with this release?

SR: Lots. The main addition to this set – because we couldn’t resist – is a new 4K restoration of Wolfshead. This was a Robin Hood TV pilot shot in 1969 but never screened on television – it was eventually bought by Hammer in the early 1970s for use as a support feature in cinemas. It was made by John Hough after working as director on The Avengers for two years and he brings all that offbeat style with him. I’d argue that it’s the best TV pilot that never went to series. It is also the most recent Hammer Robin Hood production to date and so gives the set a nice symmetry. We’ve also included the VHS version of this pilot for fun – so that fans can get a sense of how it was previously seen before this brand-new restoration.

There are, of course, new commentaries on both The Men of Sherwood Forest and Wolfshead, alongside the above-mentioned programme on Doreen Carwithen and further content on Hammer swashbucklers, Val Guest, the transition from black and white to colour in British film, an archive video interview with John Hough and another jam-packed 120-page booklet covering both productions.

Director Val Guest (centre) with his two stars. He called the movie ‘a merry romp’ and spoke warmly about its production.

HN: Talking of Val Guest, I’ve read a couple of old interviews with him where he’s so positive about the experience of making movies for Hammer during this era. Stepping back from The Men of Sherwood Forest for a second, how would you characterise 1954 (the year of the film’s release) for the studio?

SR: 1954 was actually an inflexion point for Hammer. The main Robert Lippert co-production deal was coming to an end and all of the British film companies were very scared at the potential impact that the advent of ITV would have on cinema revenues when it began transmissions the following year. This is why, if you look at Hammer’s filmography, you’ll see that in 1954/5 they had decided to shift focus to creating short support features (mostly musical) as that’s where they thought the market was going. Luckily, the success of The Quatermass Xperiment at the end of 1955 caused them to change tactics pretty much overnight, but it’s obvious with hindsight that they were on the wrong road until that happened. 1954 is a very important year for Hammer as that could, in a Sliding Doors moment where they didn’t adapt Quatermass for film, have been the end of them.

The men of Sherwood Forest… John Van Eyssen (far left) returned to Hammer for Quatermass 2 (1957) and to play Jonathan Harker in Dracula (1958).

HN: What’s been your favourite thing about working on this particular project?

SR: Trying to think up the additional programmes and articles that the fans and collectors will enjoy and which we know they have come to expect from a Hammer release. Obviously, with most Hammer productions there are no cast and crew alive to be able to contribute, so we have to be inventive as to how we offer up information, insight and context on behalf of these people who are no longer around to do so themselves. It’s very much a privilege and a responsibility to create this new content, but also a lot of fun.

The women of Sherwood Forest… Eileen Moore with Vera Pearce, who plays Elvira (right). An Australian stage and film actress whose movie career began in silent pictures, Pearce made her first onstage appearance with the World's Entertainers in Sydney whilst only 5-years old.

HN: And finally, at the risk of sounding pretentious, this is a film that can be viewed through many prisms. There’s its importance as a Hammer production, especially with its ‘firsts’ as we discussed. There’s its place within the broader Robin Hood mythology and ongoing historical legends the character inhabits. And, of course, quite aside from these and other relevant aspects, The Men of Sherwood Forest is a cracking movie that it’s hard not to be entertained by. So, sum it up for us! Complete this sentence: You’ll enjoy this release if…

SR: ...you have warm, nostalgic recollections of watching Sunday afternoon matinees on BBC-2 as a kid. If you approach the film with that mindset then I’m sure it will be your favourite release of ours to date.

Big thanks, as always, to Steve Rogers for sharing his time and knowledge. We’ll be bringing you more information about this release as it emerges, and you can keep bang up-to-date across the board by registering for Hammer’s regular newsletter. And don’t forget, you can also check out other titles in the Limited Collector’s Edition range, plus much more, over at the online shop.