The Forgotten Faces of Hammer: Cybill Shepherd - Part One

The Forgotten Faces of Hammer is an occasional series in which we focus on actors who, although well-known, are overlooked in terms of their achievements with the studio. Last time around we featured Ursula Andress and here we’re celebrating another icon of the silver screen – Cybill Shepherd.

There’s a certain irony in the fact that a movie centring on a railway journey proved to be the terminus for Hammer’s post-war iteration. After producing several hundred movies, shorts and featurettes, the organisation which reinvented the horror genre and had transformed and defined British cinema, was finally derailed after 32 continuous years of business.

But despite the financial problems that swirled around its final days, and the loss of key members of staff, Hammer’s (temporary) last hurrah was far from a train wreck. In fact, this farewell film isn’t simply an overlooked gem of a thriller, it’s possibly the studio’s most influential work in terms of its impact on cinema and to a lesser extent, 80s television. Yes, really. So climb aboard as we celebrate its leading lady and the 90 or so minutes of a lavish, bygone age which form 1979’s The Lady Vanishes.

It started so well. Cybill Shepherd’s first film was the instant classic, The Last Picture Show (1971), a movie that critics loved so much they actually struggled to express their depth of appreciation for the work. Roger Ebert hailed it the best film of the year and called it, ‘…above all, an evocation of mood. It is about a town with no reason to exist, and people with no reason to live there. The only hope is in transgression.’ The Los Angeles Times crowned it ‘the most considered, craftsman-like and elaborate tribute… to what the movies were and how they figured in our lives.’

As Jacy in The Last Picture Show, a character Shepherd described as ‘a self-absorbed ice princess’.

Shepherd plays Jacy Farrow in the movie, one of the drama’s central characters. It’s a testament to her immersion in the role that when she met Richard Nixon, the then President of the United States knew the film well, but didn’t initially recognise her. Shepherd later admitted she felt embarrassed by this, but it’s been pointed out that Nixon simply didn’t associate the confident woman he was chatting to with the naïve schoolgirl she creates in the picture.

The role won her awards and a profile, and during production she famously began a relationship with the film’s director/co-writer, Peter Bogdanovich, a move that was to have a profound influence on her career and the way she was perceived by the public and industry insiders. Affairs within the film business are commonplace, but Bogdanovich, a married man over ten years older than Shepherd, seemed to flaunt their friendship and unfortunately, this played badly with pretty much every observer, which after the movie’s success, was pretty much everyone. Hollywood legend Cary Grant even phoned his old friend to warn him against such openness. ‘Stop telling people you’re so in love and so happy,’ he urged Bogdanovich, reasoning most of his audience were neither of these things.

Recalling that period years later, Moonlighting exec Glenn Gordon Caron stated, ‘I think she [Shepherd] was someone the public decided they didn’t like. She and Peter would go on The Tonight Show and there was a sense of these two people [were] filled with entitlement, and I think the public, at a point, turned on them.’

Marketing material for The Last Picture Show. The movie earned Shepherd her first Golden Globe nomination, in this instance in the ‘New Star of the Year – Actress’ category.

Shepherd herself later characterised their overt and extravagant lifestyle as ‘disgusting’, but it’s worth remembering that when The Last Picture Show launched she was only 21-years old, and a stranger to such heightened levels of show business scrutiny. To an extent she was protected by those around her and therefore, initially at least, unaware of the toxicity that was building. But after one of her jokes bombed as she presented an Oscar at the 1972 Academy Awards, the director Billy Wilder wrote in Variety, ‘Hollywood is now united in its hatred of Peter Bogdanovich and Cybill Shepherd.’

It was suddenly hard to escape the sense of animosity levelled at her. Cybill Shepherd had gone from being in the eye of a hurricane to the centre of a storm.

Judith Crist warned that knives would be out for her, and so it proved. Critics discussing her subsequent movies seemed intent on reviewing her relationship status as opposed to the work she’d delivered. And those knives were sharp. One correspondent called her Bogdanovich’s ‘well-publicized but untalented girlfriend’, and Vincent Canby, who had once showered her with praise, now rained on her parade, declaring that casting her in At Long Last Love (1975) ‘…is like entering a horse in a cat show.’

Later that year, however, Shepherd’s agent, Sue Mengers, took a call from a young director who requested ‘a Cybill Shepherd type’ for his upcoming movie. Mengers is said to have replied, ‘How about the real thing?’ and her client was duly put forward for the part. The director was Martin Scorsese, the film became Taxi Driver (1976) and Shepherd proved a sensation. Reviewers’ reluctance to praise her was almost palpable and plaudits were often dished out in the most mealy-mouthed fashion. ‘Cybill Shepherd, as the blond goddess is correctly cast,’ Ebert admitted, before adding, ‘for once, as a glacier slowly receding toward humanity.’ The fact that neither Shepherd or Betsy (the character she plays) is remotely glacial in the movie is apparently neither here nor there. That was a view of Shepherd as she was perceived to be ‘in real life’ and critics had been confusing the actor with her roles ever since The Last Picture Show.

Shepherd with Martin Scorsese during the shoot of Taxi Driver. The movie was filmed in NYC during a severe heat wave with temperatures exceeding 100°F in some parts of the city.

Betsy is the gutsy and intriguing campaign volunteer, so central to the eponymous cabbie’s descent into murder and ascent into phoney herohood. Despite Jodie Foster and Robert De Niro taking the lion’s share of laurels, it was hard to deny that Shepherd’s nuanced and crucial turn was anything less than superb.

She’s great in her next film, the heist movie Special Delivery (1976). Writing in 2017, critic Richard Winters reflected, ‘I know I’ve bashed her in some of other film roles, but here her personality fits the part as she creates a kooky lady with a nice balance between being both eccentric and conniving.’ She starred opposite Michael Caine in her following project, the breezy crime flick, Silver Bears (1978). ‘Cybill Shepherd hams it up as a romantic interest, and is good value,’ Film Authority noted when reviewing it, adding the picture is ‘a quietly enjoyable diversion for adults with a bit of patience.’

Shepherd’s friend Orson Welles once professed that actors are as much defined by the roles they don’t play as the ones they do. Sure enough, it’s the pictures she missed out on during this period that catch the eye. For instance, she turned down the part of Linnet (eventually played by Lois Chiles) in the well-received Death on the Nile (1978) and tried but failed to win a role in Family Plot (1976), the comedy thriller that became Alfred Hitchcock’s final film. In her strangely beguiling autobiography, Cybill Disobedience, she refuses to place the blame on poisonous critics or Bogdanovich. Instead, she puts the Cybill into responsibility and repeatedly cites her own incapacity to ‘play the game’ in Hollywood. Time and time again, she concedes, her own outspoken and honest approach seemed to cost her good roles, but it’s possible her own insecurity was also a factor.

Example. She fought hard for the role of Daisy in The Great Gatsby (1974), but when director Jack Clayton asked for a screen test, she refused, allegedly telling her agent, ‘Can’t they see I’m perfect?’ However, a new light is shone on her refusal when examining her later rejection of a similar request for Moonlighting. After turning down that plea she admitted to a studio exec she’d been apprehensive about the test shoot in case the producers saw her onscreen and changed their mind about casting her, a concern the exec dismissed as ‘absurd’.

Absurd or not, her reluctance in the mid-70s feels understandable. After being lauded for The Last Picture Show she’d been skewered for subsequent performances. Taxi Driver provided some sort of redress but the two films she followed it with, although serviceable enough, hardly capitalised on her success with Scorsese. Her screen time in Silver Bears is nowhere near as sizeable as the film’s trailers and publicity would have us believe, and for all its individuality, Special Delivery isn’t really that special. Little wonder she felt bruised and cautious. In a surprisingly candid interview in 1975, when asked about bad reviews she admitted, ‘I’d love to be loved by everyone. I mean, who wouldn’t?’ Again, it’s instructive to bear in mind the young woman who’d received such vitriolic attention was still in her twenties.

By this point Shepherd’s career was already a cauldron of contradictions. She’d been lauded and lampooned, praised and decried. Her CV boasted classics and mediocre movies. There was a sense the public didn’t warm to her, but they couldn’t get enough of her, a fact exploited by the marketing of films she appeared in. When her first album, Cybill Does It...To Cole Porter received some strong reviews there was a suspicion she’d swap movies for music, a medium she expressed an abiding affection for. Her future seemed uncertain.

And then came the call from Hammer.

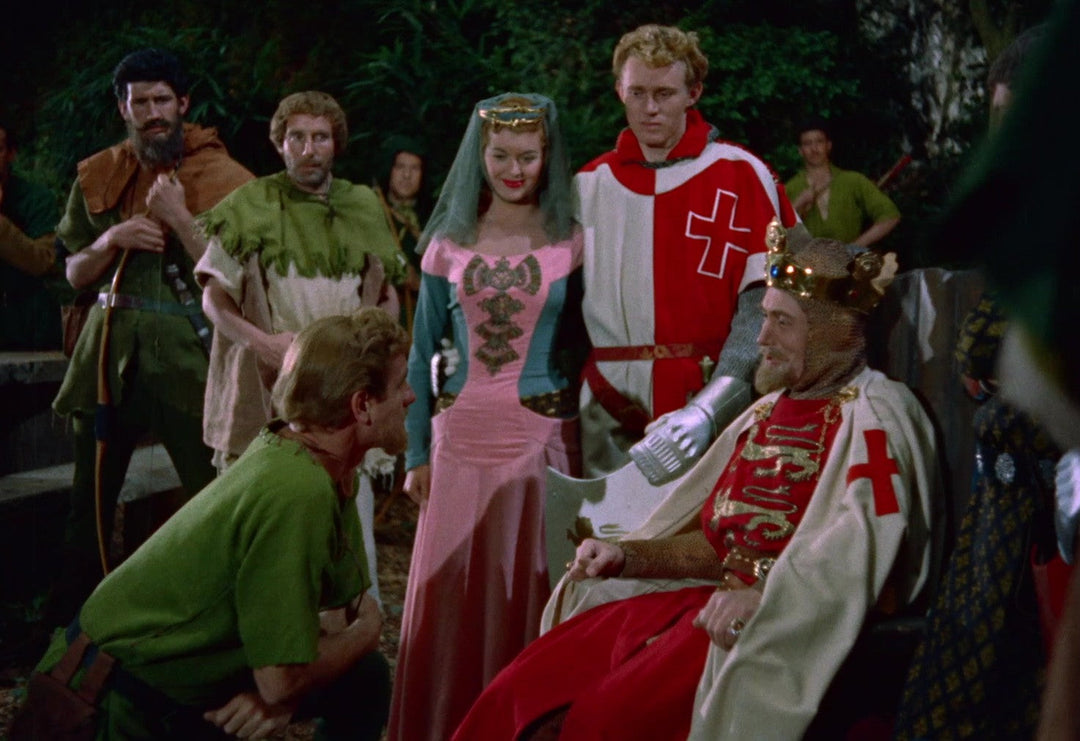

The Lady Vanishes was Shepherd’s first film for Hammer and she was given the role made famous by Margaret Lockwood.

The decline of the British film industry in the mid-late 70s forms a gloomy but fascinating story. However, it’s not a tale to be told here. Suffice to say, Hammer had not been immune to the challenging environment and even before a single cinema ticket was sold for The Lady Vanishes, the company had slid into bankruptcy.

In many ways the work was a fitting au revoir. Anthony Hinds, such a stalwart of Hammer’s post-war era, had by this point relinquished his executive role and his fellow veteran, James Carreras, had also moved on. But his son, Michael Carreras, had been involved in over 100 Hammer productions before taking the reins for The Lady Vanishes and other returnees included Musical Director Philip Martell, Sound Editor Alfred Cox, and Casting Director Irene Lamb.

Pleasingly, in front of the camera, Herbert Lom was also back in the fold. His most recent appearance for Hammer had been as the titular The Phantom of the Opera (1962), but here, as the velvet-voiced baddie, he more readily conjures up memories of his first Hammer role, Roger Ford, the perfidious puppet-master in Whispering Smith Hits London (1952). For many, Arthur Lowe falls into the category of ‘I didn’t know he was in any Hammer films…’ and although hardly a regular for the studio, he’d played Mr Spiros in their 1974 comedy, Man About the House.

The characters played by (l-r) Herbert Lom, Elliott Gould and Cybill Shepherd wonder if they’re on the right track in The Lady Vanishes.

Carreras had spent about three years attempting to get the project off the ground, suggesting it was close to his heart and represented the direction he thought he could take the company. Originally envisioned as a picture for US television, the Rank Organisation, who held the story’s remake rights, ultimately financed it as a cinema feature film, and Hammer went down their familiar route of putting American actors in lead roles to ensure a transatlantic relevance and appeal. In previous decades stars from the States including Barbara Payton, Brian Donlevy, Dan Duryea, Robert Preston, Stefanie Powers and even Tallulah Bankhead and Bette Davis had been recruited to perform a similar function and now it was the turn of Elliot Gould and Cybill Shepherd to fulfil that brief.

The production was directed by Anthony Page, had a relatively healthy budget of £2 million and was shot in Pinewood Studios and on location in Austria. Filming began in late ’78 and its royal premiere took place the following Spring, on May 8th, 1979, at the Odeon Leicester Square in London. (Photos taken immediately after the first screening show Queen Elizabeth II smiling broadly, nattering with a very healthy looking Shepherd who, at the time, was 7 months pregnant with her first child.) The following day, the film opened across the country. It’s fair to say that no one could have anticipated what followed, both in terms of the movie, its extraordinary ramifications and the next chapter of Cybill Shepherd’s turbulent life and career…

In Part Two of The Forgotten Faces of Hammer: Cybill Shepherd, we’ll be looking at the making of The Lady Vanishes, covering the problems on set, the singing between shots, how Hammer set their version in a more dangerous world, and why Michael Carreras insisted his remake was not… a remake. We’ll examine the fallout from the film and, of course, track Shepherd’s unpredictable career as she took on everything from Broadway to the Blue Moon Detective Agency!