Coming Soon: Quatermass 2

It seems like the old aphorism is true. You wait years for an iconic alien threat in 4K, and then two come along in relatively quick succession. Yes! Here at Hammer News we’re delighted to confirm that the next release in Hammer’s Limited Collector’s Edition Range is the acclaimed Quatermass 2 (1957), featuring the return of Brian Donlevy as Bernard Quatermass.

We spoke to Hammer’s Steve Rogers, one of the people responsible for this latest release, about the film itself, its impact, additional material and much more.

Hammer News: Let’s start with the film itself. For anyone who’s never watched a Quatermass movie or serial in their life, what’s Quatermass 2 about?

Steve Rogers: A lot of stories, including the first Quatermass, show the effect of an alien invasion as it’s happening. Quatermass 2 boxes a bit more cleverly than that – here the aliens invaded a few years ago and no-one noticed. And now they’ve started to take over key members of society.

HN: Aside from that narrative twist, what sets it apart from all those other ‘alien invasion’ movies that proliferated in the 50s?

SR: Most alien invasion films, and not always from the 1950s, are often quite juvenile in their outlook, but Quatermass 2 is first and foremost a dramatic masterclass in paranoia. The fact that the root cause of it all are big, blobby space monsters is almost incidental, really.

‘Quatermass, Quatermass… why do I know that name?’

HN: I’ve got a lot more questions about Quatermass 2, but could I ask you about Hammer’s release of The Quatermass Xperiment (1955)? How did the launch go? What kind of reaction did it generate?

SR: The launch went exceptionally well. Fans and collectors alike seem very happy with our new, ongoing Limited Collector’s Edition Range across the board but, obviously, the Quatermass films are special to a lot of people and there was a great deal of excitement at the sheer wealth of content we’re featuring in the set. Our release of Quatermass 2, of course, matches the high bar set with Xperiment.

HN: That’s good to hear, and thanks for the update. Back to Quatermass 2… Its predecessor, The Quatermass Xperiment (1955), was produced without direct input from Nigel Kneale, the man who created and wrote The Quatermass Experiment for BBC tv in 1953. But this time around Kneale co-wrote the script. Do you think that makes this a very different picture to the first movie? I suppose I’m asking – can you tell Kneale was more heavily involved in this production?

SR: I think so, yes. Kneale softened Donlevy’s character slightly from the first film and used the opportunity to streamline and enhance the elements that worked best from the second BBC series while jettisoning those that didn’t (all of episode six, basically). Though he had to ensure that the second film matched the tone and style of the first for obvious reasons, the finished product very definitely comes across as a Kneale script.

Vera Day (above) was spotted by director Val Guest on the opening night of Wish You Were Here, at the London Casino in 1953. This led to her big screen debut in Guest’s ballet-based drama, Dance Little Lady (1954).

HN: He [Nigel Kneale] said, ‘All the Quatermass things have been very much tied to their time.’ How’s that the case for Q2?

SR: The 1950s was a time when post-war anxieties ran high and fear of the “other” was a daily occurrence, whether that was due to race, class or politics. That decade was also, arguably, the heyday of the first wave of speculative sci-fi. In Quatermass 2, Kneale – a master dramatist first and foremost – plucks both of these elements out of the zeitgeist and delivers a punchy line in Cold War paranoia played out through the prism of science fiction.

(l-r) Brian Donlevy, William Franklyn and Bryan Forbes in Quatermass 2.

HN: It’s got another strong cast, including William Franklyn, Bryan Forbes and of course, Brian Donlevy. Lomax, the harassed police inspector from The Quatermass Xperiment, is back, but this time he’s played by John Longden, probably best remembered as the detective in Hitchcock’s Blackmail (1929). Kneale preferred his interpretation of Lomax. Why do you think that’s the case?

SR: I imagine that’s more to do with the actor rather than the performance. Jack Warner turns in a creditable performance in Xperiment, but he’s obviously playing Jack Warner and not Kneale’s character. Longden was a notable character actor of some repute and obviously played the part as written.

Sid James taking a call on set to explain – again – the twist ending in The Man in the Black (1950).

HN: Sidney James (credited as Sydney James) plays Jimmy, an old school reporter. He’d appeared in Hammer productions previously, turning in a very solid performances, particularly in The Flanagan Boy (1953). He’s by no means the star of Quatermass 2, but he’s memorable and likeable. Do you think James was underrated as an actor?

SR: Certainly. At this point in his career, Sid was a jobbing character actor who bounced between drama and comedy like many others in the industry. He turned in a notable performance as the dramatic lead in Hammer’s The Man In Black, as well as support in films like The Flanagan Boy, but his success in Hancock’s Half Hour on both radio and television eventually boxed him into comedy roles. I don’t think he minded from an artistic point of view – he was more interested in paying his bookie than giving award-winning performances.

HN: Two fairly trivial questions now… I love the pre-title sequence! It gets things off to a flying start and we’re immediately reassured that Quatermass is back and he remains as energetic and urgent as ever. It’s also good to see he’s honed his ability to get into trouble, to the point that he’s in the thick of the action within one minute of the movie starting! Were pre-title sequences common in the 50s? Or would this have jolted viewers (in a good way)?

SR: It’s what is known as a “cold open” – a scene designed to grab the audience by the scruff of the neck and drag them straight into the plot. The gold standard for this is, of course, the Bond films and it’s very often used these days on both film and television but, back in the mid 1950s, it was mostly a televisual device designed to hook the viewer before the first set of adverts appeared. Its use in a film of this vintage, especially a British film, is vanishingly rare and, as such, very powerful.

Quatermass 2 begins briskly, with the Professor literally crashing into action to ensure an exciting start to the sequel.

HN: And was this the first sequel to have what is essentially the brand name followed by ‘2’ as its title?

SR: That’s what everyone says, but that’s partially a bit of revisionism. The ‘2’ in the title actually refers to Quatermass’s lethally unstable nuclear-powered rocket, though of course it stands double duty to let viewers know that it’s a sequel they’re watching. At the time of writing this second story Kneale wasn’t even sure if there would be a third (it would take another three years for him to figure that one out) so there were certainly no brand or franchise considerations.

HN: Quatermass 2 performed very well at the box office, but The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) was released the same year and proved to be a phenomenon that changed the course of Hammer and horror. Without The Curse of Frankenstein do you think the studio would have made more films in the vein of Q2? Possibly even some more in the series, with Donlevy starring and Val Guest directing?

SR: Undoubtedly. Xperiment was followed very swiftly by a film called X the Unknown, which is basically a Quatermass film in all but name, and Hammer also adapted another Kneale science-horror BBC play into a film called The Abominable Snowman. So that’s the direction they were heading until The Curse of Frankenstein blew the doors off – and if the world wanted full colour gothic horror then Hammer would readily oblige.

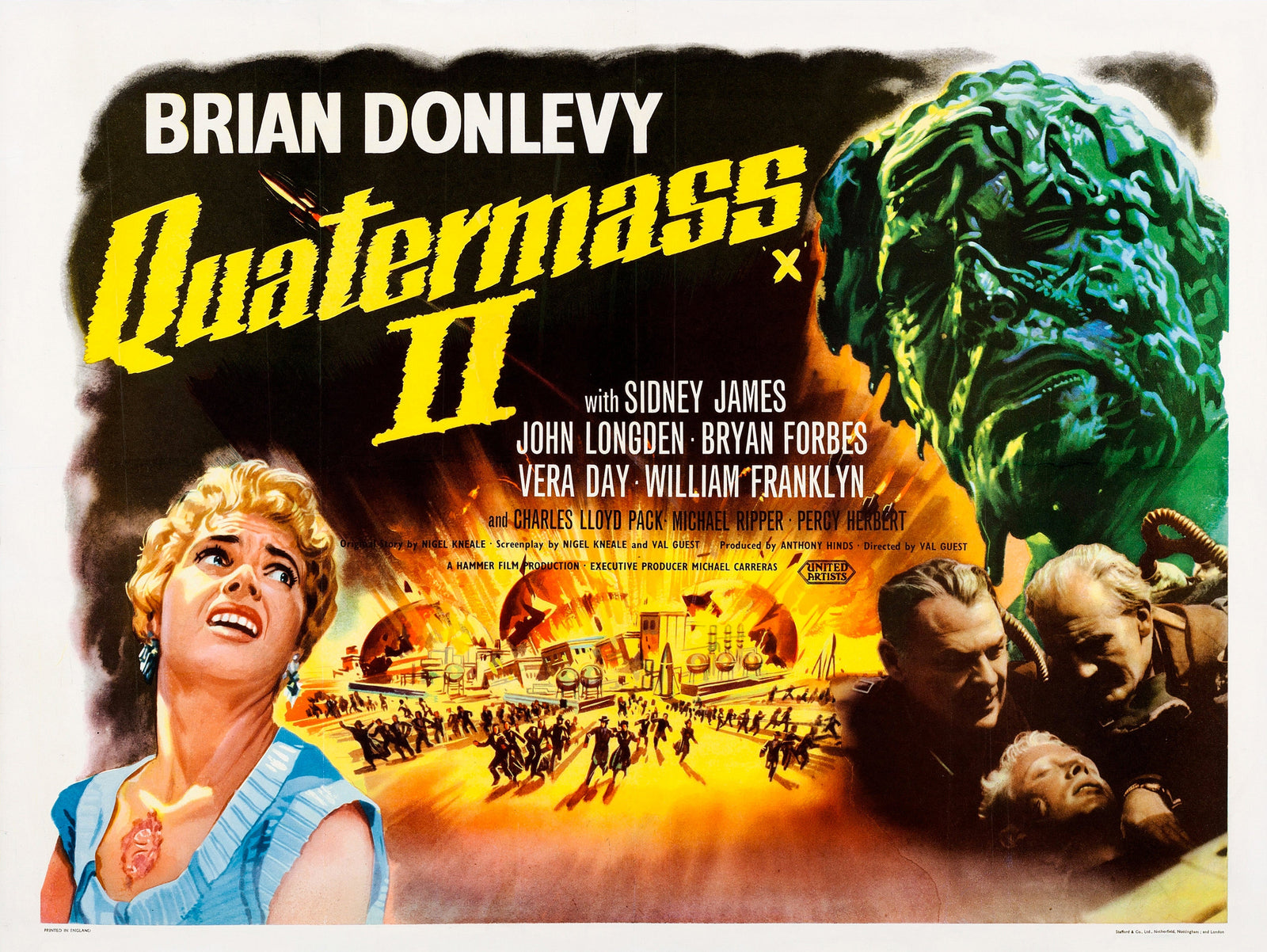

This eye-catching poster, used for promoting Quatermass 2 in France, features some gorgeous and imaginative artwork.

HN: It’s often claimed that Quatermass 2 was the first production for which Hammer pre-sold the distribution rights in the States, with James Carreras giving them to UA in return for very healthy, upfront financial input. Is that your understanding? And going forward, did this liberate Hammer?

SR: What happened was that the success of The Quatermass Xperiment got Hammer noticed by the major players and Hammer’s chairman James Carreras, a world-class dealmaker and showman, grabbed that opportunity with both hands.

His previous co-production deal with American producer Robert Lippert, between 1951 and 1955, had allowed Hammer to create a run of B-movies with baked-in US distribution. But Xperiment’s success allowed Hammer to get into main feature production and, over the coming decade, allowed them to create an unrivalled run of popular films with financial support from Columbia, United Artists, Paramount, Warners, Universal and others. Of course, nothing’s for nothing and all this funding came with caveats, but it certainly liberated Hammer enough for it to start striving for greater things.

HN: Hammer’s recent release, The Quatermass Xperiment, had a huge array of additional content, so I have to ask - could you give us an idea of the material that we’ll be seeing with Quatermass 2?

SR: We’re taking the approach that the Donlevy Quatermasses are a matched pair and so the supporting material for Quatermass 2 is very definitely in step with Xperiment. We’ve got the second part of our newly-created Kneale documentary, a documentary on the making of Quatermass 2, a great little featurette on Brian Donlevy, some archive interviews with Val Guest and some long-thought-missing film materials that even include some incredibly rare clapperboard shots. That’s all alongside the BBC series, the 1970s comic adaptation and another large booklet offering varied insights into the film, the series and other context.

Director Val Guest, seen here during the shoot for Quatermass 2.

HN: Wait! I genuinely didn’t know all six episodes of Quatermass II (the BBC tv series that served as the source material for Hammer’s Quatermass 2) would be included in this release. We have to talk about that! Rudolph Cartier really upped his game (which was already as ‘up there’ as ‘up there’ got in the 50s) for this one. Nigel Kneale praised Cartier for delivering such an ambitious piece of television. Simply from a production point of view, how was Quatermass II ahead of its time?

SR: Television production in 1955 was still performed and broadcast live from a BBC studio. Even though it was then eight years since television’s post-war revival, austerity and necessity led BBC drama productions down a road where they were often damned by reviewers as “stage on TV”. This was somewhat self-inflicted as a lot of production staff had moved across from BBC radio and were less than adventurous when it came to creating content.

That’s where Rudolph Cartier came in – an Austrian film director who worked at UFA studios in Berlin, he left after the Nazis rise to power in the 1930s, went to Hollywood and then settled in Britain. In 1952 he told the BBC’s Head of Drama that their output was dreadful and was hired to address the situation. Over the next two decades he pushed boundaries in terms of budgets and production, but his name will forever be linked with Kneale’s for the work they did in the 1950s.

By the time Cartier was planning Quatermass II, he’d got the cause celebre adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four under his belt (another Kneale collaboration) and was, I think, feeling bullish. The lessons he learned on that production and on the first Quatermass led to extensive location filming and a much more dynamic production than Experiment.

HN: The original Quatermass, Regnald Tate, sadly died shortly before filming was due to begin on this one, and was replaced by John Robinson. How does his interpretation of the Professor differ from Tate’s?

SR: I think John Robinson doesn’t get much love in the “who’s your favourite Quatermass?” sweepstakes, but he turns in a strong performance given that he took up the role at short notice and was obviously concerned, as any actor would be, about picking up the reins on an established and popular character. He certainly got good reviews at the time but, with André Morell’s subsequent barnstorming performance in Quatermass and the Pit and the only Quatermasses circulating in the zeitgeist for the next five decades being the film ones, Robinson’s performance sort of fell through the gaps. Including it in this release allows a new audience to judge both the production and his performance for themselves.

Val Guest (r) on location with Stanley Baker for Hell is a City (1960), one of the many, many films Guests directed for Hammer.

HN: And more Val Guest interviews are always welcome. His early body of writing work includes Oh, Mr. Porter! (1937), The Ghost Train (1941), Inspector Hornleigh Goes to It (1941) and Back-Room Boy (1942). These are all absolute corkers. And The Runaway Bus (1954) is a delight! I know you’ll roll your eyes, but with a bit of tweaking that could have been a cracking Hammer movie! Okay, bit of an unfair question, but after Q2 and The Abominable Snowman (1957), why didn’t he do more stuff with Hammer?

SR: Well, he did do more work with Hammer - but he didn’t really work on any of the gothics as I don’t think his taste ran to that sort of horror. He scored subsequent hits for Hammer with the war films The Camp on Blood Island and Yesterday’s Enemy, a brace of nautical comedies, the superb Hell is a City and gaslighting psychoterror The Full Treatment. His theatrical last hurrah for Hammer came a decade later with cavegirl pic When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth – though he was called to the colours once more in the mid 1980s to direct a trio of TV films for Hammer House of Mystery and Suspense. So Hammer certainly wasn’t done with Val Guest once Quatermass 2 was in the can but, as the company moved away from science horror and into the gothic arena, Guest just seemed to naturally gravitate towards projects that he enjoyed on a more personal level.

HN: It’s strange, I never really consider Guest to be a ‘Hammer director’ in the same way I’d think of, say Terence Fisher or Freddie Francis, but when you reel off his work for the studio like that, it helps put his contribution into context. Okay, let’s wrap it up by getting your personal view on something relating to this new release… What’s your favourite moment in Quatermass 2? (Spoiler alert! The following reply touches on plot points that lie outside the general premise of the film…)

Typically understated marketing for the film’s release in Mexico.

SR: If you’d asked me that previously I’d have probably said Broadhead being covered in black goo or poor old Sidney on the wrong end of a tommy gun but, having recently rewatched the film for the first time in twenty years, I now have to say it’s neither of those. It’s the scene in the pump house where Quatermass and the rioting villagers stare in horror at the dripping pipe and Quatermass says, “That pipe has been blocked with human pulp!” That moment, that line of dialogue and the way the actors react – that’s pure drama.

As always, huge thanks to Steve Rogers for giving up his time and sharing his expert insight into all things Hammer.

You can find out more about the The Quatermass Xperiment or investigate the entire Quatermass Collection which includes Blu-rays, DVDs and other merch. We’ll be bringing you more info on the release of Quatermass 2 soon, and you can sign up for our newsletter that’s got you covered for news, features and lots more Hammer goodness!