The Forgotten Faces of Hammer: Sixty Years On… She Who Must Be Remembered

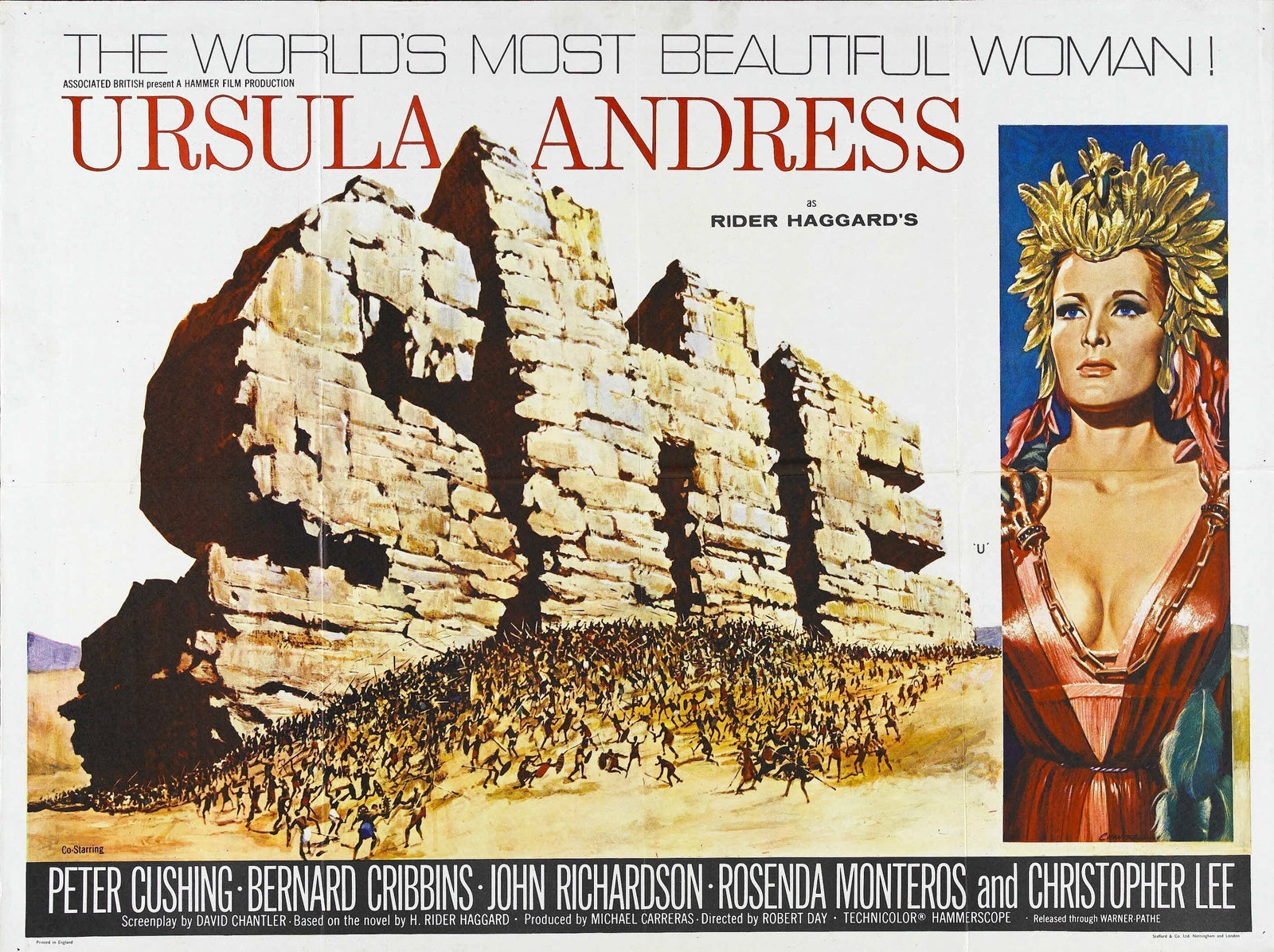

The Forgotten Faces of Hammer is an occasional series in which we shine a light on actors whose achievements with the studio have slipped into undeserved obscurity. We begin by focussing on the star of what was Hammer’s most expensive production at the time of its release… the woman who brought the mighty and magnificent She (1965) to life 60 years ago: Ursula Andress.

There’s a moment in the BBC’s 1994 spoof chat show, Knowing Me, Knowing You… With Alan Partridge, where the host, hypnotised by Tony Le Mesmer, believes he’s talking to Ursula Andress. ‘Ursula, I’ve always wanted to meet you!’ he gushes. ‘I can’t believe it’s you… I love all your films! I’ve got all of them, from Dr. No…’ He pauses. Racks his brain. Gives up, and concludes with a lame, ‘right through to all the others.’

It's a joke, of course. All the others. But it’s one that feels credible, simply because Andress is arguably more famous as an icon than an actor. It’s a lingering injustice that’s existed since her breakout role of Honey Rider. Her arrival in Dr. No (1962) has become the acknowledged gold standard of cinematic entrances. During her first moments in an English language movie we see Honey emerging from the Caribbean Sea, carrying conch shells and singing Underneath the Mango Tree. It’s a striking scene that, to this day, Andress remains associated with. Or perhaps ‘bound to’ would be more accurate. Because in the public’s mind and a thousand clip shows, Ursula Andress is forever stepping from those warm, blue waves; over 50 years on and she still hasn’t made it back to dry land.

Even the rest of the movie feels immaterial due the ivory cotton material she was wearing. ‘The bikini made me into a success,’ she later commented, adding that as a result of playing Honey Rider in EON’s first Bond movie, ‘…I was given the freedom to take my pick of future roles and to become financially independent.’

Dr. No was re-released in the States shortly before She hit US cinemas for the first time, further boosting the profile of Andress (above).

One of those roles was Ayesha in Hammer’s blockbuster hit, She. Based on H. Rider Haggard’s famous novel, known alternatively as She and She: A History of Adventure, this torrid tale of immortal love was first serialised between October, 1886 and January, 1887. Published in book form later that year, it remained hugely popular, never out of print, and seemingly never off the minds of Hollywood producers. Inevitably, this story of an ageless, powerful queen ruling a hidden city had already been filmed many times before Hammer got its hands on the rights. But neither Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein nor Bram Stoker’s Dracula were strangers to the silver screen prior to The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958), suggesting the public’s familiarity with a mythology could help, as opposed to hinder a remake’s chances of success.

Hammer’s biggest problem was actually, as they later admitted, casting the eponymous lead. Get that wrong and the film fails to make sense. But that scene would prove pivotal to the casting process. ‘As soon as we saw Ursula Andress walk out of the sea in Dr. No,’ one of the studio execs recalled, ‘we knew there was only one woman to play Haggard’s Queen. We had to wait two years before she was free of other commitments, but it was worth it.’

Promotional material reported that the cloak Andress is seen wearing in this shot contained 3,000 feathers.

Hammer had pitched the project to Disney and Universal, who’d both passed, before a deal was cut with MGM, securing a budget that was significantly higher than any that had been lavished on their previous movies. This allowed for location filming in Israel and some impressive sets. This sense of scale clearly appealed to studio execs and referencing She in the Kinematograph Weekly, producer Michael Carreras opined ‘There’s no doubt the future lies with bigger productions’.

His optimism must have felt well-placed. The film was shaping up to be a visual triumph, as critics later agreed. ‘Handsomely produced,’ the New York Times conceded, with The Daily Cinema praising its ‘opulent settings’.

Just the job! On location with Bernard Cribbins who teamed up with Peter Cushing again shortly afterwards, saving the planet in Daleks - Invasion Earth 2150 A.D. (1966).

She also boasts an excellent cast. Peter Cushing is on fine form and Bernard Cribbins steals so many scenes he could have been charged with grand larceny. Christopher Lee and André Morell are powerful players, but in terms of delivering a captivating presence, it’s hard to see beyond Ursula Andress. The role of an apparently immortal, god-like queen would have led many to overplay key scenes, but Andress recognises Ayesha’s confidence and plays the ruler with a firmness, clarity and sense of certainty. It makes her later vulnerability all the more effective, and helps her to come across as more human than previous interpretations.

For example, in the 1925 version, co-directed by Leander de Cordova and G. B. Samuelson, Betty Blythe plays the Queen with an other-worldly quality that emphasizes her supernatural side. Her take works well for that production and proves haunting and memorable. But Andress’s Ayesha offers us a down-to-earth deity. She is flesh, but also fire, burning with quiet rage for those who displease her; blazing with passion for the man she adores. She’s all-powerful and impotent; horrifically cruel and hopelessly in love.

A poster for the 1925 version of She, which proved to be the final (to date) silent feature to use Haggard’s novel as its source.

It may initially sound absurd, but her performance has a Peter Cushing quality to it. Directors often praised the Hammer veteran for his ability to make any line convincing. As Lizbeth Myles wrote in Uncanny Magazine, ‘Cushing’s presence in a film means that no matter the nonsensical depths to which it may sink… there’ll be smashing scenes that rise above it thanks to the talent, commitment, and sheer believability Cushing imbues in even his most outlandish roles.’

The director of She, Robert Day, was blunter. ‘Peter Cushing,’ he said, ‘gets away with the most melodramatic lines because he probably believes them himself.’

But isn’t the same true of Andress in She? Her character says things like, ‘there are times when the flame turns cold’ (really?) and ‘The old man who came out of the desert showed only me the secret of eternal life. He knew that I was the one in the world chosen to partake of that light magic…’ Despite all that endearing hokum, Ayesha somehow retains her truth and royal bearing. Clearly we’re in fantasy territory, yet she feels authentic within that context.

But back in 1965, Andress received few plaudits and although the film performed exceptionally well at the box office, many reviewers voiced a preference for the earlier, RKO version. Critic Bosley Crowther was typical. Passing judgment on the Hammer iteration, he harrumphed, ‘…it isn’t even as good as the last remake of She done with Helen Gahagan in 1935’.

Promotional material for the 1935 version of She. The Film Daily acknowledged its ‘mammoth spectacle’ but found it ‘overtalkative’.

To be fair, that black and white version is a full-on ride and a half. Its producer, Merian C Cooper, damned it as the ‘worst picture I ever made’, although that seems grossly unfair on his own movie. It’s overblown and over theatrical, but that’s part of its charm. Some of the sets are awesome, Max Steiner’s stirring music is gorgeous, and the ever dependable Nigel Bruce is, well, the ever dependable Nigel Bruce. Visually it’s a fever dream punctuated by moments of lucidity; Flash Gordon meets Rider Haggard with Gahagan turning up the vamp levels to 11. What’s not to love?

The point is, however, both versions work well despite being very different productions. The 1935 picture is enormously watchable, but it’s a deliberately OTT affair that creaked under the weight of budget problems, scenes that had to be cut at the last moment, ludicrous limitations imposed by the Hays Code, and stagey performances. 1965’s She is a big-budget blockbuster with internationally admired stars like Andress, Cushing and Lee. Location shooting in the Negev desert, ambitious sets, grand costumes by Carl Toms and Roy Ashton, and James Bernard’s sumptuous score all make this an extravagant treat.

A US poster for She, released in America just a few weeks after its mid-April premiere in the UK.

The public ignored the critics and Hammer’s She proved a massive hit. Marketing for the movie tended to focus on its leading lady, with her fellow stars not even featured in the majority of posters. So the prospect of Andress brought the crowds, and the performance of Andress made a sequel starring her a no-brainer for Hammer, with one duly announced - Ayesha – Daughter of She - in July, 1965. But Andress declined every offer to tempt her back. Some reports suggest she disliked the script (initially titled She, Goddess of Love) but whatever the truth of her reluctance to return, She was such a smash that a follow-up eventually went ahead without her.

Despite the best efforts of ‘the new She’, played by Olga Schoberová (credited as Olinka Berova), and the support of a strong cast including André Morell, Colin Blakely, George Sewell and the returning John Richardson as Kallikrates, without Andress the film didn’t entice audiences, and critics savaged The Vengeance of She (1968). Sometimes you only realise how good something is when it’s missing. Case in point – the presence of Ursula Andress. Long after the sequel disappointed at the box office, The Magnificent 60s noted tactfully, ‘Berova, while attractive enough, lacks the screen magnetism of Andress’.

The Vengeance of She turned out to be Olinka Berova’s only Hammer movie. It was also André Morell’s last Hammer hurrah, and John Richardson’s final film for the studio.

And although reviewers in the 60s were more or less dismissive of Andress, focussing on her anatomy rather than her acting, recent critics have been more insightful in their analysis of her work, and specifically her role in She. Horror Cult Films pointed out, ‘Andress looks terrific as usual and displays a kind of vacant cruelty which works for her part’. And writing for The Magnificent 60s, Brian Hannan shrewdly observed, ‘Ursula Andress is stunning, every inch a goddess and yet believably mortal. Her looks tended to mask her abilities and while she rarely received credit for her acting she holds her own in some redoubtable company.’

Despite these twenty-first century re-evaluations, it could be claimed that in terms of Hammer, and indeed many of her films for other studios, Andress remains unjustly forgotten. And although she’ll always be remembered as Honey Rider, had Alan Partridge known anything about cinema he could have reeled off a number of wildly popular productions - aside from She - that she made shine. From to the pop culture explosion that is The 10th Victim (1965), the acclaimed war film, The Blue Max (1966) and the dark, suspenseful heist flick, Perfect Friday (1970), to the breezy good humour of Fun In Acapulco (1963) and Casino Royale (1967), her works are varied, vivid and at their best, utilised her skill to create movies which proved successful both critically and financially.

Her later pictures included The Fifth Musketeer (1979) and Clash of the Titans (1981) in which she played Aphrodite opposite Laurence Olivier’s Zeus.

In promotional material for She, Andress talked about her acting style. ‘My best takes are the first,’ she revealed. ‘Repetition distracts from the quality of my performance. Ayesha in She was a difficult part because this mysterious queen is 2,000 years old and I had to be very stylized.’

Andress’s guiding principles appear to be simple ones. ‘My philosophy,’ she once revealed, ‘is to be honest, happy and live life.’ It seems to have worked. Val Guest, who directed her in Casino Royale, was open about her charisma and the way this international star was able to get along with everybody. ‘I don’t think I have ever met someone who was so universally loved by everyone in a studio,’ he admitted. ‘They’d all do anything for her and this is really quite something.’

But before we leave She, the voice-over artist (and actor in her own right) Nikki van der Zyl, should also be acknowledged. An intuitive and sensitive performer, she provided the voice of many characters including Honey Rider in Dr. No, Ayesha in She, Samantha Steel in Funeral in Berlin (1966) and Jill Masterson (the woman who’s murdered by a liberal coat of sparkly paint) in Goldfinger (1964). Van der Zyl worked on several Hammer productions but remains best-known for her contribution to the James Bond franchise, on dubbing duties for over fifteen years in many of 007’s pre-Dalton adventures.

The double bill of One Million Years B.C. and She: catnip for fans of John Richardson.

The success of She paved the way for the studio’s so-called ‘Cave Girl’ series which included favourites like One Million Years B.C. (1966) and When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1970). But six decades on from its cinema release, it also stands up as a piece of action-packed drama, a rich, tragic love story that it’s easy to get lost in. At once a guilty pleasure and a gilt-edged one. Reviewing it in for Empire in 2000, William Thomas wrote that ‘…this stays memorable for Andress’s performance as the commanding Ayesha… it still has an epic quality.’

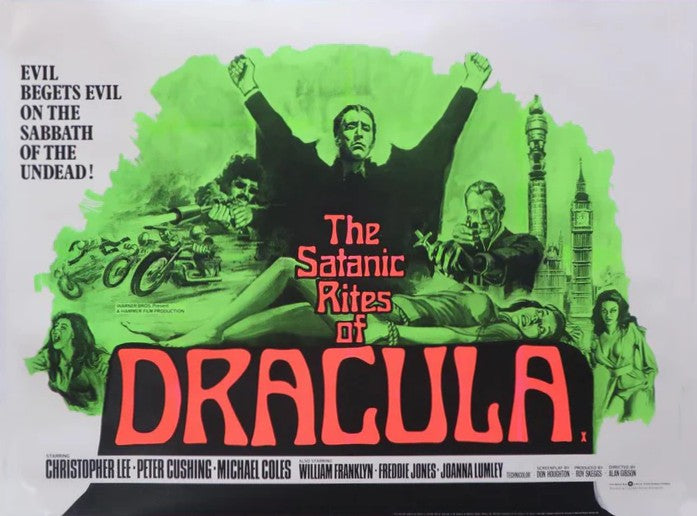

Christopher Lee was a friend and relation of James Bond’s creator, Ian Fleming. In the early 60s the author suggested he play the titular Dr. No in the planned movie adaptation. Despite Lee’s enthusiasm, the role ultimately went to Joseph Wiseman.

There’s a moment in She where Bernard Cribbins’s character glimpses Ayesha for the first time. He gives a typically 1960s response, murmuring, ‘Blimey… They just don't make ’em like that anymore, sir.’ He’s referring to Ayesha, of course, but his words could equally apply to the film itself. It’s sixty years since She first wowed audiences across the world, and even if the magical flames ensured Ayesha was not, in the end, immortal, at least Andress’s performance and the movie it graces may yet prove to be eternal.

And it’s true, you know. They really don’t make them like that anymore.

If you’d like to read more about Hammer stars whose work for the studio is occasionally overlooked, we discuss Stefanie Powers and the great Tallulah Bankhead in Re-opening: Fanatic (1965), a vast array of actors who featured in early productions in The Genres that made Hammer - Part One: An Origin Story, and with the recent release of the newly restored, 4K edition of Four Sided Triangle (1953), we celebrate the career of its leading lady in Barbara Payton: Hollywood, Hammer and Playing the Cards.