The Curious Case of A Man on the Beach

The film archives of Hammer Studios contain many unexpected treasures, and a gorgeous, gritty featurette from 1955 is certainly one of its most intriguing. A Man on the Beach is an often overlooked and fascinating thriller, but is its biggest mystery a twist that wasn’t in the script?

A Man on the Beach (1955) begins deceptively, with a sequence following a vintage car being driven through attractive continental scenery whilst old-fashioned music, jaunty and upbeat, plays over the opening credits. Considering what follows, this is genuinely bizarre, as if the filmmakers started crafting a sequel to Genevieve (1953) before reading the screenplay and finding out the film’s about murder, theft, home invasion and borderline sadism.

We soon arrive at a casino where Maxie, a man disguised as a woman, assaults one of the managers, steals a case of cash and escapes in the car, driven by his accomplice. Reluctant to share his loot, Maxie fights with and kills his partner-in-crime, but injured in the tussle, he only makes it as far as a nearby beach before collapsing. He finally manages to drag himself to the only house he can see, and when its owner returns a classic game of cat-and-mouse ensues. Maxie is armed and takes a vicious delight in taunting his ‘prisoner’, but the mysterious homeowner has secrets of his own...

Cross-dressing criminals, heists gone wrong and the ‘twists’ that round out A Man on the Beach were nothing new, even in the mid-50s. But the film is much more than a sum of its more familiar elements.

The work itself emerges as a glorious oddity. It’s a mere 29 minutes long and stands as one of Hammer’s earliest films to be shot in colour. It’s also directed by one of cinema’s most critically acclaimed and nuanced directors, Joseph Losey. At first glance it seems an odd vehicle for an auteur who remains best-known for thoughtful, multilayered takes on the British class system with The Servant (1963) and The Go-Between (1971), and in all honesty, there’s little doubt he took the job out of professional necessity.

Blacklisted in his own country, the States, for his left-leaning politics, he was forced to relocate to Europe to continue his career. His ‘escape’ is often portrayed as a tragic exclusion, but Losey himself seemed sanguine about the upheaval he endured. Towards the end of his career, when asked about the blacklisting that forced him from America, he replied, ‘Without it I would have three Cadillacs, two swimming pools and millions of dollars, and I’d be dead. It was terrifying. It was disgusting, but you can get trapped by money and complacency. A good shaking up never did anyone any harm.’

Losey’s style makes A Man on the Beach a visual treat, at once fluid and unsettling. It has the long-takes often associated with his best work and critics have praised the film’s pace and mise-en-scene. It contains long periods without dialogue, followed by scenes where the two central characters trade brutal barbs with a kind of controlled ferocity. It’s compelling, if a little unoriginal in parts. It would be lunacy to describe it as one of Losey’s best pieces, but this captivating curio clearly benefits from having such an accomplished director calling the shots.

However, the fact that it was directed by a giant of cinema is not the central factor in terms of its importance to Hammer, and indeed, to horror films in general. The fact it was written by Jimmy Sangster gives A Man on the Beach its lasting significance.

It was based on the short story, Chance at the Wheel (originally published as Menace at the Casino) by the British author, Victor Canning. A phenomenally prolific and successful writer of thrillers, humorous novels, children’s books, radio plays and stage plays, Canning has lapsed into obscurity and is now probably best remembered for his 1972 thriller The Rainbird Pattern. Adapted by Ernest Lehman, it became Family Plot (1976), the final movie project completed by Alfred Hitchcock.

Victor Canning (1911 – 1986), the highly successful author who wrote the short story that formed the basis for A Man on the Beach.

Sangster took Chance at the Wheel, made some shrewd changes to the plotline and its characters, and delivered his first ever screenplay. His tweaks to the original story are interesting. Crucially, Canning’s narrative doesn’t involve the chauffeur. In the source material, Max meets the ageing, enigmatic homeowner (named Charnot in the original) following a tyre blow out that leads to a car crash. The film version allows us to see Maxie’s willingness to murder - killing his colleague who seems touchingly fond of him, without a second thought - and therefore raises the stakes for when he’s alone with the older man.

In Sangster’s iteration the audience is left in no doubt that this thief-on-the-run would shoot the stranger if necessary, giving the second half of the featurette an effective will-he-won’t-he dynamic. The screenplay also removes several scenes from Canning’s short story that may have signalled one of the final twists, and Charnot becomes Carter, an English doctor, ‘married to the bottle’. A self-professed recluse when we meet him, he was clearly once a man of means who stayed at ‘the best hotels’ and wore Saville Row suits.

Maxie is eager to taunt Carter about what he perceives to be a fall. ‘You were well-heeled once, all right. Or was it well-kept? Maybe a woman threw you out! Or did a younger man move in?’ He predicts the former physician will soon go mad and is dismissive of his gentle poetry.

Carter, meanwhile, refuses to play the part of terrified captive, and speaks his mind to his unexpected guest. ‘I suppose you’re happiest when you’re perpetrating some form of physical violence…’ he tells Maxie. ‘You’re much too self-confident. You’re conceited. You have an almost indecent affection for yourself.’

That self-confidence will ultimately play a part in Maxie’s downfall, whereas his own insults, hurled at Carter, are without basis and simply betray his ignorance of the situation, showing how blind he is regarding the doctor’s history.

Sangster’s ability to write cracking dialogue that switches between tense and immediate exchanges, to more cerebral concerns (Carter pontificates upon the nature of violence at one point, for instance) would serve him well in his later scripts for Hammer.

Early in his Hammer career, Sangster worked on The Lady Craved Excitement (1950), a light crime-comedy starring Michael Medwin.

A fan of films since childhood, Sangster worked with the studio long before A Man on the Beach, employed as a Third A.D. on Dick Barton Strikes Back (1949) and rising through the Hammer ranks with films including The Man in Black (1950) and Whispering Smith Hits London (1952). The decision to move him from the floor to behind a typewriter was a fortunate one, but what triggered that reallocation is unknown.

Many years later, when quizzed about the film’s screenplay, Sangster admitted, ‘I have no recollection of writing [A] Man on the Beach at all. None at all! It’s quite a nice, little picture. I saw it the other day…’ He recalled it featured Michael Ripper (as Maxie’s chauffeur) and added with a smile, ‘Everything had Michael Ripper in it!’

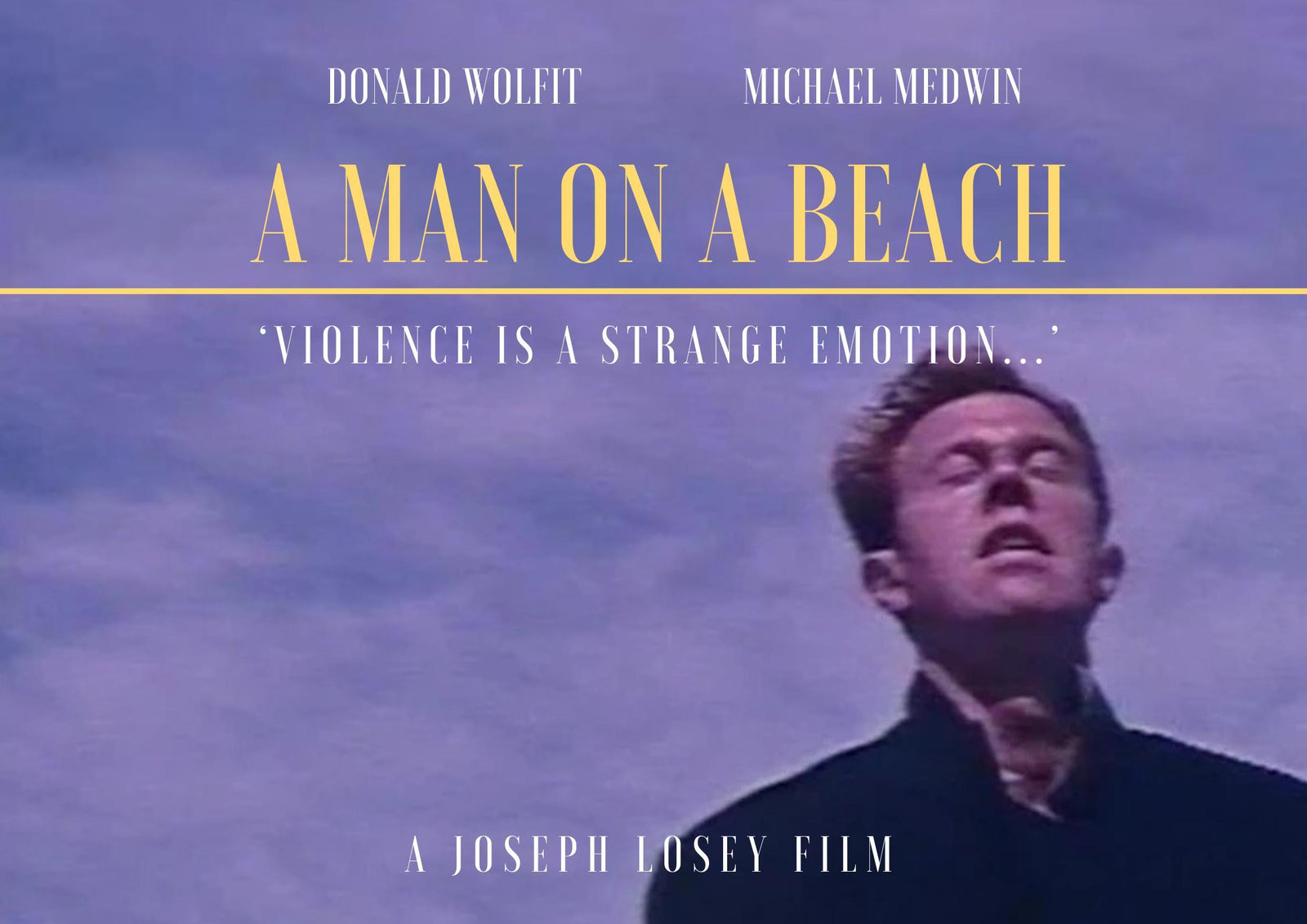

Starring Michael Medwin as Maxie, and Donald Wolfit as Carter, the featurette was produced by Anthony Hinds.

Later, following the success of The Quatermass Xperiment (1955), Hinds, studio exec Michael Carreras and Sangster discussed possibilities for a follow-up after it became clear that the use of its eponymous hero wouldn’t be immediately viable. Together they came up with the premise of X The Unknown (1956) and it was Hinds who told Sangster to write the script for the project. Again, years later, Sangster recounted what followed.

‘I said, I’m not going to write it! I’m not a writer - I’m a production manager! They said We’re paying you as a production manager. Go away and write it and if we like the script, we’ll pay you for that, too! So, I went away, I wrote it, they liked it and they paid me – 450 quid, actually, and suddenly I was a writer!’

It’s an anecdote Sangster recalled on multiple occasions, and it indicates the importance of A Man on the Beach. Had the influential Anthony Hinds been dissatisfied with his screenplay for that work, it’s highly unlikely he’d have pushed for him to write a script for a movie the studio had so much riding on.

Sangster’s screenwriting credits include the classic Dracula (1958).

But the producer’s instincts were sound. Sangster’s script for X The Unknown resulted in another hit for Hammer and his writing career was fully underway. He turned in several more scripts for the studio, including two of its most important films, The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958). The man who claimed not to be writer also penned many successful books and episodes for hit US series including Kolchak: The Night Stalker and Wonder Woman, as well as numerous film scripts for non-Hammer projects.

If his work on A Man on the Beach had failed to impress Anthony Hinds and others, it’s possible that his vast, impressive body of work would never have been typed into existence.

Or would it? Did A Man on the Beach really turn the tide?

There’s one other possibility, of course. Rewind to Sangster talking about his early writing days. In 1993 he recalled telling Anthony Hinds, when asked to write X The Unknown, ‘I know nothing about screenwriting…’ which feels odd for someone who’d already written a screenplay.

Rewind further back, to Sangster discussing the 1955 featurette: ‘I have no recollection of writing [A] Man on the Beach at all…’ Again, this could be considered odd for someone who retained a good recollection of lesser events which had happened long before the mid-50s. During that same interview he added, ‘It had Joe Losey… who was originally engaged to do X The Unknown, which was my first, which I consider to be my first screenplay.’

What if Jimmy Sangster considered X The Unknown to be his first screenplay because it was his first screenplay? At a time when Jospeh Losey was still problematic to work with due to his blacklisting, could Hammer have decided that naming him as director and writer was a step too far? It’s worth noting that he was due to direct X The Unknown but dropped out early in the shoot. As Vic Pratt noted in a piece for the BFI, ‘Losey left the production somewhat abruptly – supposedly with pneumonia, but, according to Sangster, removed from the project owing to star Dean Jagger’s reluctance to work with a ‘red’ director.’

‘Can anything escape its terror?’ Well, yes. Its original director, for starters.

Certainly, the screenplay for A Man on the Beach contains many themes and motifs that feel typical of Losey. Were they included in the script because he included them?

Any suggestion that Jimmy Sangster didn’t write (or entirely write) A Man on the Beach does nothing to diminish his skill or standing. In Hammer Films: An Exhaustive Filmography, Deborah Del Vecchio and Tom Johnson hail him as ‘the horror film genre’s greatest writer’, an accolade few would disagree with.

Whoever wrote A Man on the Beach, it remains a mesmerising thriller, a moment in film history that feels unlike any other. And pondering the possibility that Sangster was not as involved in the screenplay’s creation as some would say does little, aside from shake up a few lines in a few old film books.

And as a wise man once said, a good shaking up never did anyone any harm.