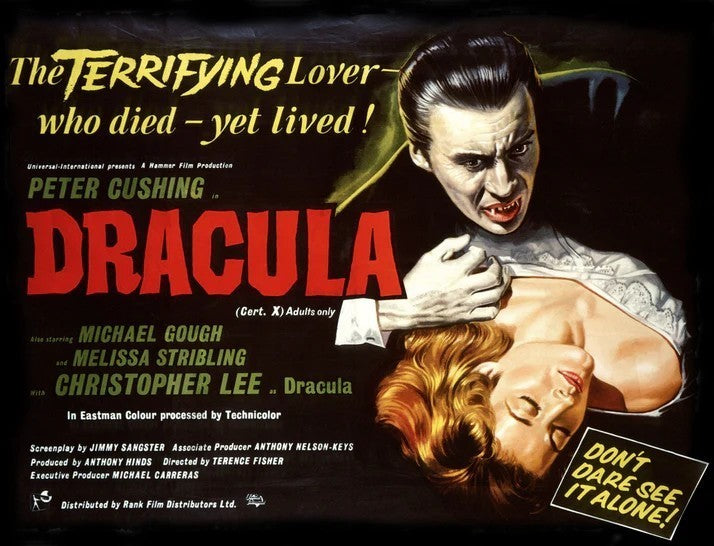

I am Dracula… The Scene that Started a Legend

In recent weeks we’ve looked at various Hammer movies and their ramifications, the careers of their stars, specific eras within the studio’s history and indeed, what lies ahead for the company. But here we’re focussing on just 73 seconds; on a single scene that changed cinema forever - the moment when Christopher Lee announced to the world, ‘I am Dracula!’

Dracula (1958), released in the US as Horror of Dracula , has been hailed as the most celebrated film Hammer ever made. Many critics contend it’s one of the great, if not the greatest horror movies of all time, and there’s little doubt it stands as one of the most atmospheric and compelling gothic thrillers ever produced. The work technically premiered at the Warner Theater in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in early May, 1958, but on 25 May it received its high profile New York premiere at an event designed to publicise its general release. Studio execs James Carreras and Anthony Hinds were in town for the midnight screening at the Mayfair Theater, alongside actors Christopher Lee (making his Dracula debut in the picture) and Peter Cushing, the silver screen’s new Van Helsing.

Hopes were high for the film, the first to depict the Count in colour. Could it rival the enormous success Hammer had achieved with The Curse of Frankenstein (1957)? The New York event offered a chance for the people behind the movie to gauge an audience’s reaction to it; not the professional prose of newspaper critics, but the actual, physical response engendered in men and women, sat in the crowded dark, waiting to be scared and entertained.

Peter Cushing’s interpretation of Van Helsing differed enormously from the character as written by Bram Stoker. Younger and more serious, his vampire slayer proves a fitting foil for the Count.

In Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing and Horror Cinema , Mark A. Miller describes the screening. ‘Then, as the film finally began, the worst happened. The audience, expecting a typical schlock horror film, noisily laughed and jeered at the film. Lee and Cushing were mortified. Lee contemplated leaving but Cushing persuaded him to hold on for one more moment. The dark outline of Count Dracula appeared at the top of the stairs on the large Mayfair screen. A dramatic, electrifying chill silenced the audience as Christopher Lee’s Dracula made his way down the stairs… He had them under his spell.’

This account serves to underline the scene’s importance and power. There are several stand-out moments in the movie, from Dracula’s first attack – a passage of strikingly visceral frenzy – to the glorious, climactic confrontation between Van Helsing and his nemesis. On the other hand, the introduction of Dracula is the antithesis of action-packed. There’s no blood. No battle. No special effects. In fact, it’s just two men introducing themselves with cordial civility, and yet somehow, it emerges as one of the picture’s most memorable highlights.

On the run-up to it, Jonathan Harker (John Van Eyssen) arrives at Castle Dracula, where a letter from his host informs him of a slight delay, but essentially urges him to make himself at home. Whilst waiting for Dracula, an agitated young woman (Valerie Gaunt) arrives and begs Harker for his help. Before he can properly question her, she races away. And at this moment, Dracula’s introduction begins. The narrative of the scene is simple. Harker’s host descends a staircase. They exchange courteous introductions before Dracula helps his guest, carrying the other man’s luggage up the staircase. They walk further into the depths of the castle and… that’s it.

Fuelled by much more overt drama, the passage prior to Dracula’s arrival (featuring Valerie Gaunt and John Van Eyssen, as seen above) contrasts to what immediately follows and offers an effective counterpoint to the introduction of Lee’s character.

But the cast and crew ensured it was enough to enthral and win over that Mayfair audience, and audiences ever since.

Any discussion of what makes it so potent must start with Christopher Lee. His portrayal - a genuine revelation. Physically, he is imperious. Tall, slim and handsome, he conveys a naturalness not previously associated with the character. Much has been made, quite rightly, of the sense of nobility Lee brings to the part. Author Jonathan Rigby mentioned that in his opening scene, for instance, he delivers his lines ‘with a throwaway aristocratic insouciance’, immediately distinguishing himself from every other character in the movie and reminding the audience of the character’s origins.

Lee himself observed, ‘I tried to make Dracula a romantic and tragic figure. Someone you could feel sorry for.’ It’s a point he made on many occasions but these aspects are not revealed during his introduction. Quite the reverse – here he’s presented as a man completely in control. More than this, he plays the exchange with Harker with a tremendous sense of purpose and although his guest isn’t lumbered with any comedy flaws – there’s no bumbling incompetence or clichéd English ineptitude, for example – he’s clearly no match for Dracula. Lee’s sense of command makes this evident, almost before a word has been exchanged.

And this gives us a clue to Lee’s expert handling of the role – he manages to draw us in, to impress us, even without (apparently) trying. It’s a trick very few actors can achieve with such deftness. Lee’s first moments as Bram Stoker’s most famous creation are enough to convince us that this is a compelling new iteration of an old fiend. He transforms into the Count, which is perhaps why he never became typecast by the part. He may have donned the billowing black cape on many more occasions (citing ‘emotional blackmail’ from James Carreras as the reason for his returns), but he remained strangely disentangled from the role. Associated with it forever, but never ensnared by it. He could be Sherlock Holmes, Mycroft Holmes, Rasputin, King Philip or Count Dooku, each walks free from the shadow of Dracula – a feat never truly achieved by Bela Lugosi, his most notable predecessor in the Drak Pack.

Hollywood Reporter enthused, ‘Excitement and intrigue permeate the film,’ calling it a ‘A lavishly mounted, impressive production.’

Even Peter Cushing was struck by his old friend’s transformation. ‘Christopher Lee gave a remarkable performance as Dracula, quite remarkable. He is an enormously charming gentleman, but when he became that terrifying creature, even I jumped.’

Cushing’s choice of words, choosing ‘when he became that terrifying creature’ as opposed to ‘when he played that terrifying creature’ is telling.

In short, when Christopher Lee declares, ‘I am Dracula,’ we believe him.

Blaskó Béla Ferenc Dezső (better known as Bela Lugosi) faces Arthur Lucan (better known as Old Mother Riley) in My Son, the Vampire (better known as Mother Riley Meets the Vampire).

We’d had other Draculas, before, of course. Lugosi had played him in Universal’s Dracula (1931) and the public had instantly embraced his interpretation. He’d reprised the role on screen only a decade prior to Hammer’s Dracula , in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948) and played an ostensibly similar character only six years earlier in 1952’s Mother Riley Meets the Vampire (also known as Old Mother Riley Meets the Vampire ). He’d also played the Count on stage during the 50s, so not only was his take on the role considered to be definitive, it was also relatively recent, still fresh in the public’s consciousness.

Variety had even claimed, ‘It is difficult to think of anybody who could quite match the performance in the vampire part of Bela Lugosi…’ and years later, Christopher Lee noted, ‘He had this demonic quality and those extraordinary eyes… But I felt the performance was more rigid than I’d been led to expect… Lugosi’s Dracula was not physical at all.’

Lee makes sure the opposite is true of his version. Even in his opening scene there’s an impressive athleticism to Dracula. The way he moves, even when carrying the luggage, is smooth and decisive. Almost balletic. Strength is implied with every detail. It’s an unspoken threat; a threat he makes good on soon after, to quite devastating effect. Lee’s impressive deportment was not lost on director Terence Fisher who once acknowledged, ‘He moves like a dream for a tall man.’

Fisher and the movie’s writer, Jimmy Sangster, must also take plaudits for the success of the scene. It begins almost exactly five minutes after the opening titles fade out, and we’ve hardly had time to digest Harker’s encounter with the distraught and mysterious young woman before Dracula arrives. His appearance immediately wrongfoots us. We may have expected Harker to chase the stranger who begged for his help, but instead we’re suddenly introduced to the star of the show. Or rather, we’re promised an introduction, because the first reveal finds him at the top of a staircase.

Lugosi’s Dracula was all about the stares. Lee’s – all about the stairs.

The reaction shot capturing Harker’s jump scare moment sets up our expected emotional response to the sight of Dracula, but the ensuing beat subverts it.

As Fisher explained, ‘In my film, when Dracula makes his first appearance, he took a long time to come down the stairs but it seems a short time because you’re waiting to see what he’s going to look like… I’ve seen it in cinemas again and again – they [ the audience ] thought they were going to see fangs and everything. They didn’t, of course. Instead they saw a charming and extremely good-looking man with a touch, an undercurrent of evil…’

There’s no jump cut as Dracula descends the steps. Like Harker, we must wait for him – another indication of who is in control. (Image slightly brightened to highlight set details.)

Any notion of Lugosi’s eccentric, slightly bizarre portrayal, is immediately swept away. Here is a more dangerous Dracula. One who knows our ways well enough to camouflage himself with them. Consequently, the dialogue itself has a surface-level sterility.

DRACULA: Mr. Harker, I’m glad that you’ve arrived safely.

HARKER: Count Dracula?

DRACULA: I am Dracula. And I welcome you to my house. I must –

>>>PAUSE<<<

What? From his position on the upper level, Dracula must have seen Harker accosted by the frantic, desperate-looking woman who claimed she was being held a prisoner in his castle! Is neither of them going to even mention it? Not even in passing? No “That was a bit strange!” from Harker? No “Ignore her! She does the cleaning every Tuesday afternoon and she’s usually on the sauce by sundown,” (or similar) from Dracula? No. And somehow, the exchange doesn’t feel poorer for its failure to mention the stranger. The presence of the castle’s owner has made Harker forget her, and in truth, it’s made us, the audience, also push her from our thoughts. It could be argued this hints at Dracula’s mastery. He doesn’t wish to discuss the incident, so it’s as though it never happened. Right. Okay.

>>>PLAY<<<

DRACULA: …apologise for not being here to greet you personally, but I trust that you have found everything you needed?

HARKER: Thank you, sir. It was most thoughtful.

DRACULA: It was the least I could do after such a journey.

This ‘normalisation’ of Dracula is a masterstroke. Alfred Hitchcock famously pointed out that in terms of cinema, ‘There is no terror in the bang, only in the anticipation of it,’ and by giving the audience the commanding figure of Lee’s Dracula, and quickly presenting him as courteous and helpful, viewers are being primed for ‘the bang’. Made to wait for it, as Harker’s host becomes a ticking bomb, creating tension through their expectation of the explosive moment that must surely follow.

When Dracula finally bares his teeth, literally and figuratively, the impact is heightened by his earlier show of civility.

Even in 1958, thanks to a gory poster campaign, audiences would have been familiar with the fanged, blood-stained version of Dracula, but that face is hidden by a mask of good manners. We’re waiting for the disguise to be wrenched aside, and it’s a testament to the film’s prowess that when the moment comes, it doesn’t disappoint with its unbridled ferocity.

The way the introduction is blocked, and the angles Fisher uses, are also of interest. Dracula is initially above Harker, emphasising his superiority and his ‘otherness’. In fact, throughout the film he’s placed at the top of a staircase on over half a dozen occasions. In most instances, he may be above us, but he has the means to descend – to reach us for either a social nicety or a savage onslaught – at any moment.

When he initially speaks to Harker, Fisher ensures we’re again looking up at Dracula, and of course, he leads the way when he guides his guest into the heart of his home. All these touches serve to underline his command and position of strength, establishing him as both a worthy adversary for Cushing’s dynamic vampire killer, and an effective villain in his own right.

‘Christopher Lee never misses as the horrifying Dracula… [the film] will have audiences terrified in their seats from Land’s End to New York.’ – Daily Cinema

The introductory scene is packed with other pleasing details. The position of the candles, forming an obvious ‘V’ that points to Dracula is a fun inclusion, as if tiny fires of Hell are flickering towards one of their own. And there’s another minor, lovely moment as Harker gathers his belongings. Dracula’s façade slips for a split-second. Study his face as he watches the younger man picking up his books. The Count’s civility glitches, as if whatever delivers his stream of sham courtesy is momentarily jammed. For a heartbeat we see his impatience. We see his disdain. And we see, with an absolute clarity, that Jonathan Harker is in danger from the figure who has just welcomed him so graciously.

Trying to make Dracula appear at once pallid, to reflect the fact he’s undead, and healthy and ruddy, to suggest his vitality and bloodlust, must have felt a daunting task for make-up artist Phil Leakey, but he achieves it well and the two opposing elements of the character are skilfully fashioned. Much of Stoker’s description of his ‘original’ Dracula is unused. The ‘heavy’ moustache and ‘extremely pointed’ ears, outlined by Harker early on in the book, are mercifully ignored. But he also describes Dracula’s eyebrows - ‘almost meeting over the nose’ – a detail Leakey subtlety recreates. The pioneering make-up supremo remains best known for his work on The Curse of Frankenstein , but his success in bringing Dracula to life is another notable accomplishment.

Molly Arbuthnot was the Costume Designer on Dracula, Bernard Robinson the Production Designer and the camera operator was Len Harris.

Even the sound of the scene is a treat. When we first glimpse Dracula we are given his doom-laden three-note, musical motif.

Dra-cu-la!

Grand, operatic and stirring, the incidental music was written by James Bernard, a young composer who’d studied under Benjamin Britten at the Royal College of Music. He scored a BBC radio play, The Duchess of Malfi , which caught the ear of the influential John Hollingsworth who, impressed by the work, introduced him to Hammer.

Bernard had already scored four films for the studio, including The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and The Curse of Frankenstein by the time he was tasked with the music of Dracula . Critics have been unanimous in their praise for his work on the latter movie and have noted it’s richer and more ‘complete’ than his previous scores.

But after we first see Dracula and hear his motif, the music fades and we’re left with a highly effective silence. A few seconds earlier we’d heard the clatter of items falling to the floor in this cavernous room, but now, as the Count finishes his descent of the stairs we hear nothing, not even the lightest of footsteps. This noticeable quietude works well to suggest Dracula’s supernatural side, and it more than implies a remarkable stealth.

Bernard’s previous scores for Hammer included the music for Quatermass 2 (1957).

We don’t hear any more music until Dracula leaves Harker for the evening. And then, after the Englishman has been alone for less than seven seconds, the score resumes. It’s almost as though the orchestra itself was afraid of the Count and have only now dared to tiptoe back to their instruments, safe in the knowledge he’s not around.

The introductory scene ends with Dracula leading Harker towards his bedroom. Up the staircase and, ‘Unfortunately my housekeeper is away at the moment. A family bereavement. You understand?’ It’s the first time Dracula has mentioned death, and he slips it into the conversation as naturally as a comment about the weather. His directness about the demise, and his implied apathy regarding it, makes Harker’s flaccid, ‘Yes, of course,’ feel, if not appropriate, then entirely expected.

Dracula then marches along the corridor with his guest scampering in his wake. And as the two figures ascend another staircase we remain, for the first time, behind them both, static, watching the couple appear to diminish whilst they depart, as if as an audience, we are jointly reluctant to follow.

In under a minute-and-a-quarter we have met a brilliant, dangerous new Dracula who wears his character’s legacy as easily as his cape. We recognise his strength and his resolve and his cruelty and also, we can’t wait to see what will happen next!

Christopher Lee: Dracula reborn.

It remains a fascinating narrative passage. The sort that always yields something new, no matter how many times you watch it. Wait! After Dracula descends the staircase we never see the whole of the room, as we had a few beats earlier, implying Harker is trapped by his host, as if the chamber and his options are suddenly shrinking… And the colours, those fabulous Hammer colours, courtesy of Fisher and DoP Jack Asher, that seem to be simultaneously muted and vivid. How is that even a thing? And the way John Van Eyssen appears so blithe as… Oh, there’s always something fresh to enjoy in this icon-establishing 73 seconds.

Wendy Brydge, discussing Dracula as a whole for a 2017 entry in Seeker of Truth , succinctly summed up the film’s allure. ‘There are no gimmicks. There is no unnecessary violence or gore. It’s simply a well written script, played out by incredible actors operating at the very peak of their careers, all while immersing the viewer in sumptuous costumes and Gothic sets that drip with glorious Technicolor.’

Looking back at that New York premiere and the audience’s early (very vocal) derision towards the screening, Christopher Lee recalled decades later, ‘And this [ the noisy mockery ] kept going until the famous scene in which Jonathan Harker meets me for this first time, he feels the presence and he turns around and there, at the top of the stairs is this silhouette. I tell you, the place erupted. The roof nearly came off! Perhaps they expected to hear a macabre foreign voice, or see a strange looking person with a green face. I just walked down the staircase and said, “Mr. Harker, I’m glad that you have arrived safely.” And the silence was quite remarkable. From then on, we had ’em…’

And over sixty-five years later, that scene still has us, because it has it all.